Speaker: Venerable Hui Cheng

Fo Guang Shan Qishan Temple

I. Introduction

Auspicious greetings to our friends around the world. This is Hui Cheng from Fo Guang Shan Monastery in Taiwan. I hope that this online session of Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services finds you well. Last week’s session introduced morality as a prerequisite for meditation, touching on Buddhist ethical guidelines and right livelihood. This week’s session will explain the importance of a correct mindset for meditation. We will be discussing how our attitudes and goals, as well as worldview affects the outcomes of our meditation.

First, I invite you, for a few moments, to reflect on your attitudes for learning about, or engaging in meditation. Why do we meditate? What are the reasons we aspire to meditate? What kinds of benefits or outcomes do we expect? Improved health? Mental calmness and emotional balance? Happiness and peace of mind? Relaxation? The unleashing of spontaneity and creativity? Concentration? Or the discovery of life’s purpose? Most of us have our unique reasons for meditating or learning how to meditate and indeed, all of what has been mentioned are its outcomes.

However, meditation is an omnipotent tool capable of elevating us in all aspects of our lives and leads us to a mental state free from delusions and dissatisfaction, and ultimately to a state of awakening. With the limitless potential of meditation in mind, it certainly makes sense to set our goals higher, and not just on its immediate benefits. The higher our goals, the higher the potential reached. So, what is considered a higher goal and intention?

II. Right Intention and Vow

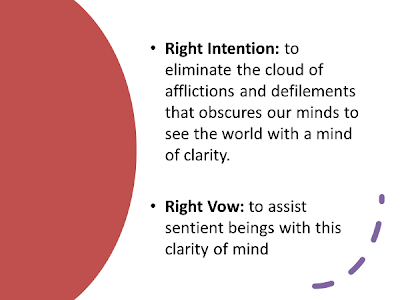

The Buddhist term for wholesome attitudes and goals is right intention and vow. The word “right” implies that not all intentions and vows for meditation are ideal. There is quite a specific framework for meditation in which right intention and right vow are defined. But generally, one’s right intention for meditation should be to eliminate the cloud of afflictions and defilements that obscures our minds so that we may see the world with a mind of clarity. Some take it a step further and develop the vow to assist sentient beings with this clarity of mind. Intentions and vows work on the mind by creating the causes for the triggering and arising of mental factors consistent with the content of our intentions and vows.

If done repetitively, we habitually condition the mind to follow such trains of thought, and grooves are created. These grooves subconsciously guide our minds during meditation towards our intended goal.

The Buddha explains right intention as threefold: (1) the intention of renunciation, (2) the intention of good will, and (3) the intention of compassion. The intention of renunciation refers to the wish of abandoning the attachments and cravings that bind us and cause boundless dissatisfaction. Venerable Master Hsing Yun reminds that all beings originally encompass the entire universe in one’s mind. However, when we attach ourselves to certain phenomena, we become overly preoccupied with them and lose the bigger picture in life.

Take the analogy of standing before an inexhaustible treasury, holding a $100 bill in each hand. Since our hands are preoccupied with grasping onto a total of $200, we cannot obtain the limitless amount of wealth before us. To access our inexhaustible wealth, our hands need to be empty. The same is true for our minds. As we set out to meditate, we should intend on abandoning all unnecessary attachments so that we may unlock the boundless potential of our minds.

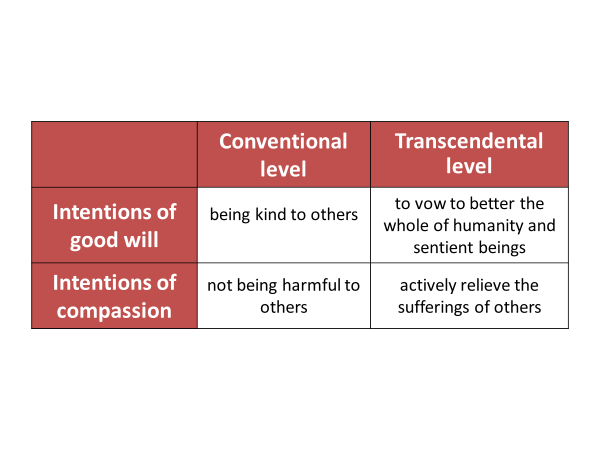

As for the right intentions of good will and compassion, there are two levels to understand them. At the conventional level, they are the intentions of being kind and unharmful to others. At the transcendental level, to not cause harm to others means to actively relieve the sufferings of others, while to be of good will means to vow to better the whole of humanity and sentient beings. The transcendental practice of right intention itself is requisite to the development of the highest omniscient wisdom which understands the fundamental oneness of all beings, though at the same time understanding the myriad ways beings manifest due to different karma.

From a Buddhist viewpoint, all beings have a Buddha nature, the potentiality to become a Buddha. We are thus in a sense not different from one another, but of the same essence. We are indeed, one.

When Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi tree by gaining perfect insight into the Truth of Dependent Origination, whereby all things manifest as a result of a culmination of causes and supporting conditions, he was hesitant to teach the Buddha Dharma to fellow humans, due to the difficulty in expressing the Dharma in a comprehensible way. However, since already realizing the oneness of all beings, Buddha was propelled by his initial aspiration to teach the Dharma in an inspiring way with the intention of liberating beings from suffering. As a result, Buddha had selflessly perfected his omniscient wisdom by virtue of attending to the needs of countless beings.

Indeed, omniscience can only be perfected when one expediently attends to the myriad needs of sentient beings, all of whom are of different inclinations.

This is likened to a teacher who is knowledgeable of his/her subject. However, to be able to teach the subject in a way comprehensible to all students employing skilful pedagogy, the teacher not only needs to be well-versed in the subject, he or she needs to understand the way the subject relates to all the different conditions and circumstances of life. The same is true with the path to awakening.

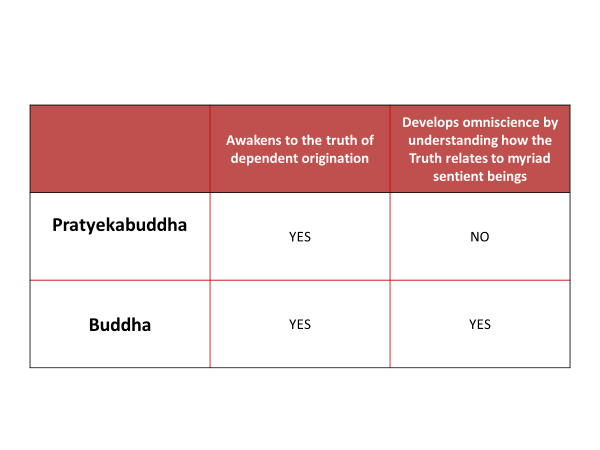

Had the Buddha failed to teach the Dharma to myriad sentient beings, he would have not perfected the path of awakening, and would have remained a pratyekabuddha, one who awakens to the truth of dependent origination without developing omniscience. In simple terms, it all boils down to the partial and complete penetration of the Truth. Here, the importance of selflessness cannot be stressed more. Since all beings are inherently one, to not realize that the liberation of all beings is necessary to one’s own path, one will never reach the highest levels of awakening. Likewise, when there is still a distinction between you, I, and them, one cannot perfect one’s character, or develop the true joy of selflessness.

In setting our goals for meditation, be brave, be altruistic, have confidence in oneself and aim high. We invite you to make the vow to meditate for the sake of the happiness of all beings.

As the “The Pure Practices Chapter” of the Avatamsaka Sutra instructs:

“Sit up straight and vow that all sentient beings may sit on the seat of Enlightenment free from attachment.”‘ It also states: “Sit in the full lotus posture and wish that all sentient beings’ goodness may remain firm and unshakable.”

With the right intention and vow of meditating for the welfare of all beings, and with the right intention of purifying one’s mind in order to do so, we will have developed the mind in a way conducive of right meditation.

The Buddhist Worldview- the basis for successful spiritual practice

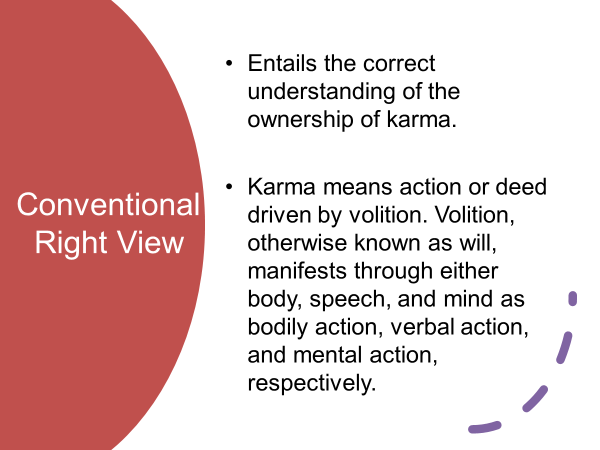

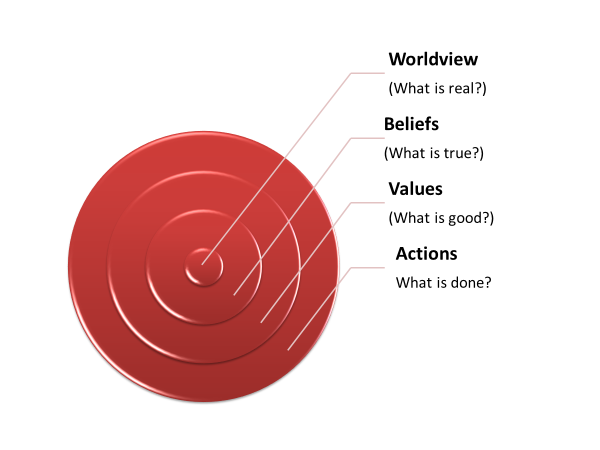

As for worldviews, Buddhism offers a framework for us to understand our own minds and the world we live in, established in Right View. In relation to Right Intention, Right View may be considered the overarching framework for practice, while Right Intention may be considered the sense of direction. In its fullest sense, Right View entails the correct understanding of all Buddha Dharma and phenomena. The type of right view necessary for the successful entry into right meditation is preliminary or conventional right view that operates within the scope of this world. This right view will be gradually perfected as one refines one’s mind through the trainings of morality and meditation and ultimately culminate in superior wisdom.

Conventional right view entails the correct understanding of the ownership of karma. Karma means action or deed driven by volition. Volition, otherwise known as will, manifests through either body, speech, and mind as bodily action, verbal action, and mental action, respectively.

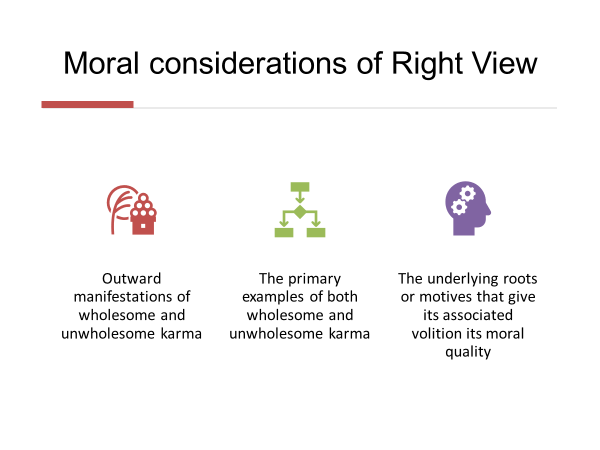

In terms of moral or ethical considerations, right view requires an understanding of:

- The distinctive features of the outward manifestation of wholesome and unwholesome karma.

- The primary examples of both wholesome and unwholesome karma, that is, the Ten Wholesome/Unwholesome Deeds.

- The underlying roots or motives that give its associated volition its moral quality.

The distinct features of wholesome karma are actions which are morally praiseworthy, beneficial to self and others, and supportive of spiritual development. The distinct features of unwholesome karma are actions which are morally culpable, detrimental to spiritual development, and conducive to suffering for oneself and others.

Examples of wholesome karma are included in the Ten Wholesome Deeds, which are:

- Not killing

- Not stealing

- Not committing adultery

- Not lying

- Not speaking harshly

- Not speaking divisively

- Not speaking idly

- Not being greedy

- Not being angry

- Not having wrong views

The above proscriptions may be interpreted in a prescriptive manner. For example, not killing means supporting life based on compassion, and not stealing may be expressed with generosity. A practical rendition of the above are the Three Acts of Goodness, namely, to do good deeds, speak good words, and think good thoughts, as taught by Venerable Master Hsing Yun. The Ten Unwholesome Deeds are the exact opposites of the wholesome deeds and are the failure to refrain from engaging in the aforementioned actions.

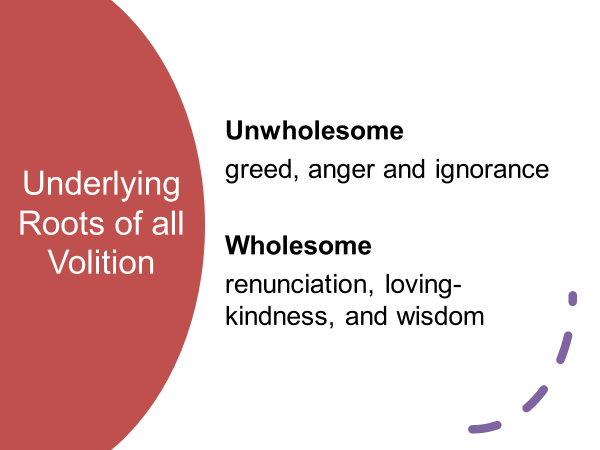

According to most traditions, the roots that underlie all volitional actions are either wholesome or unwholesome. Unwholesome roots are the three defilements of greed, anger and ignorance. Any action originating from these is an unwholesome karma, even if the outward manifestation of the action itself may seem wholesome. For example, being generous to others with ill intentions of flattery inspired by greed results in unwholesome karma. The three wholesome roots are their opposites, namely renunciation, loving-kindness, and wisdom. Similarly, a parent’s seemingly stern discipline for their child based on pure loving-kindness and wisdom may be an example of wholesome karma.

Perhaps the most inspiring feature of karma is its universal law that links actions to corresponding results. The performance of volition leaves its imprint on the mental continuum as karmic seeds, which ripen with maturing conditions. Karma is impartial, every single volition that we have ever produced have left its imprint and will continue to imprint. In general, wholesome karma results in happiness, while unwholesome karma results in suffering, either in this lifetime, or in future lifetimes.

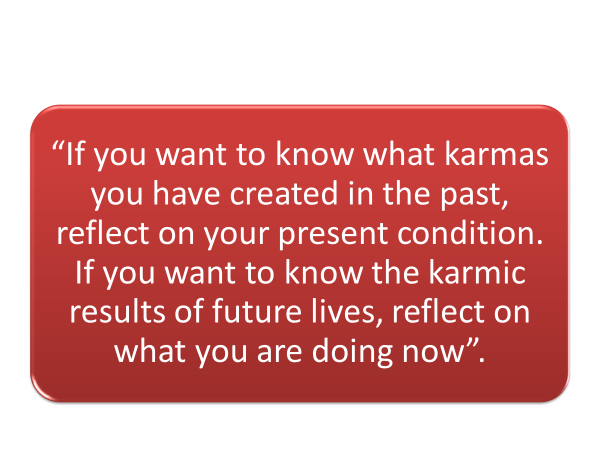

This concept is best summed up by the timeless Buddhist proverb: “If you want to know what karmas you have created in the past, reflect on your present condition. If you want to know the karmic results of future lives, reflect on what you are doing now”. Karma is universal and boundless, and our volition plays a big role in the creation of karma. To understand karma is to hold conventional right view. This understanding inspires one to align oneself with wholesomeness of mind and action, and in a sense, such knowledge makes the observing of morality effortless.

It is imperative to understand that this Buddhist worldview is not like a science experiment whereby one does not need to have faith in whether the experiment will be successful or not. When we start experimenting with our minds through meditation, we realize that our worldview is not outside of the conditions of the experiment but are the conditions themselves.

Whether we have faith in our worldview has far-reaching implications. It governs our perceptions and values, and determines the way we interpret our subjective experiences, which in turn conditions our actions and influences the decisions we make. As such, the degree of faith we entrust in our worldview utterly shapes our entire meditative experience and affects its outcomes.

In fact, Right View is the basis of all Buddhist practice, and is akin to one’s guide who shows the way to one’s intended destination. Blinded by wrong views, and in the absence of a guide, one will not only find it difficult to reach one’s destination, one may become lost.

To wrap up, this session has introduced the meditation prerequisites of conventional right view and right intention and vow. Conventional Right View is the overarching framework for practice, the rationale behind the practice of morality, as well as the shaper of our meditative experience. It inspires us to develop right intentions and vows. May we make the right vow of meditating for the welfare of all beings and have the right intention of purifying one’s mind to do so.

III. Conclusion

Thank you for joining us for session 2 of the mini-series on meditation. Session 3 will be discussing the basics of the Training of Meditation, with śamatha as its focus. If you find this Dharma service beneficial to your practice, please subscribe to the FGS English Dharma Services YouTube Channel and share it with your friends. May the merits of this session bless you with the conditions conducive of right meditation and wisdom. See you next week, Omituofo.

For All Living Beings

In For All Living Beings, Venerable Master Hsing Yun shows us that the path to a life that is wholesome, peaceful, and filled with wisdom begins by helping others. With humor and a love of storytelling, For All Living Beings, teaches us how doing the right thing can make us free, how meditation can open the mind, and how wisdom can enter every part of our life and lead us to enlightenment.

Read it here