Speaker: Venerable Hui Cheng

Fo Guang Shan Qishan Temple

I. Introduction

Auspicious greetings to our friends around the world. This is Hui Cheng from Fo Guang Shan Monastery in Taiwan. I hope that this online session of Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services finds you well.

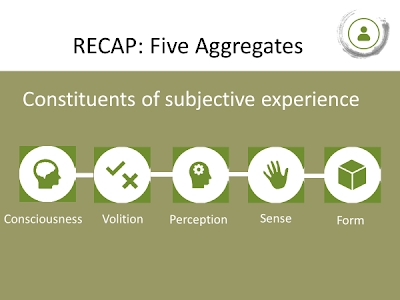

Last week’s session introduced the requisite understandings for the practice of vipaśyanā or insight meditation in relation to human sentience and the sense of identity or self, based on the Five Aggregates, which divides sentient life into five psychophysical elements of form, sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness. We may recall that this sense of self is erroneous, since it is grounded on the perception that self is autonomous, independent, and unchanging. It is a sense of self that feeds the ego and thinks that it is the most important thing on planet earth and gives rise to the underlying tendencies of craving and aversion when challenged or tempted. This awareness allows one to move onto the second level of vipaśyanā practice, that is, the clear comprehension of the five aggregates through the Four Bases of Mindfulness.

Before we continue, it is essential that we understand the context in which Buddha taught the practice of mindfulness.

During the time of the Buddha, many of whom who received such teachings were experienced practitioners who engaged in meditation all day long and had already reached advanced stages of praxis. Some were already enlightened beings. This said, some of the objects of mindfulness as prescribed by the Buddha would be difficult to understand and perhaps unrelatable if one were a beginner. As such, this session will discuss the objects of mindfulness relevant to the typical meditator of modern society.

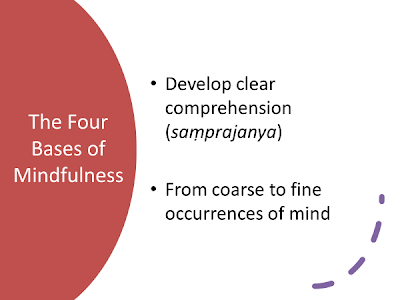

II. The Four Bases of Mindfulness: Seeing Clearly

The Four Bases of Mindfulness as expounded by the Buddha serves as the framework for mindfulness in all areas of one’s moment-by-moment life. It breaks up the practice of developing clear comprehension (saṃprajanya) into a progression from coarser or more apparent objects of meditation to finer, more subtle objects of meditation such as emotions, and finally to latent mental objects, which are usually undetectable by the untrained mind, yet they are the causes of all afflictions if they are unwholesome, and the causes of spiritual of awakening and joy if they are wholesome.

As we gently remind ourselves to be present from moment to moment, we are training ourselves to set and reset the mind on the everchanging physical and mental phenomena. Whenever we remember to be mindful, mindfulness is readily established, and allows us to be receptive and open, soft and understanding. However, mindfulness is not a forced type of hyper-attentiveness. It is more an attitude we develop, of often wishing to give rise to gentle alertness. With practice, this state of mind becomes habitual, and little effort is needed to maintain it.

With this gentle mindfulness of meditation objects, we are able to use the guidance of clear comprehension to accurately and lucidly reveal the true nature of things, empowering oneself to abandon the causes of suffering and cultivate the causes of wisdom, joy and peace.

Clear comprehension requires the correct understanding of the reality of all phenomena, sentient or non-sentient. That is, it is the ability to see the inherent impermanence, dissatisfaction, and non-self of all phenomena. As paradoxical as it may seem, impermanence is synonymous with hope, while dissatisfaction inspires motivation and compassion. Non-self allows for wonderous existence, and therefore, should be seen in a positive light.

This is true because only when things are fluid, improvement and progress may be made. Only when we are aware of dissatisfaction, will we strive to transcend it and help others to do so. Only when things and people do not have a fixed nature, can they transform into something more wholesome. Likewise, with impermanence, a dire situation may improve, while dissatisfaction inspires one to not repeat that which causes future suffering.

With non-self, we learn to disown tendencies toward greed, anger, and ignorance while adopting generosity, compassion, and wisdom. “I” becomes “we”, and “likes” and “dislikes” become: is this “wholesome” or “unwholesome”?

On a preliminary note for the practice of the first three bases of mindfulness, it is important to make the distinction between bare awareness and conceptual investigation. With the ensuing introduction to the practices themselves, please note that the Dharma concepts that accompany mindfulness do not require active discernment of meditation objects based on such tenets, rather, they need to be familiarized in our daily lives to the point they become internalized.

Come time to practice, the meditation object is viewed through the lens of the Dharma naturally and objectively. This is important since it is impossible to actively discern and be passively mindful at the same time. The whole idea of mindfulness is none other than to witness the truth of the Dharma in the workings of the subtle occurrences of the mind.

Throughout the process of developing mindfulness, the general rule is to prevent our attention clinging onto any of the objects of mindfulness. Consider oneself a disinterested observer, an observer of an autobiographical documentary who does not constantly pause or rewind the video to review a scene. This requires the constant setting and resetting of attention on the ever-changing objects of mindfulness.

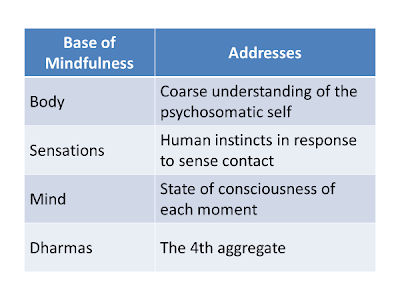

Mindfulness of the body addresses our coarse understanding of the psychosomatic self.

Mindfulness of sensations addresses our human instincts in response to sense contact and is an entry point to realizing that volitions or emotions are not necessary all the time. Note that emotion here refers to that which moves the mind.

Mindfulness of mind addresses states of consciousness of each moment, paying attention to the presence and absence of wholesome and unwholesome manifestations, allowing our minds to gently maintain mindfulness of all the aggregates.

Mindfulness of dharmas addresses primarily the 4th aggregate of volition and pays attention to the fleeting mental events. This requires acute mindfulness to detect, as they are subtle and latent mental processes.

As mentioned in an earlier session, mindfulness of the entire body is the best place to start with this practice, since it is a coarse and apparent object of meditation. It also serves as an anchor that prevents our minds from wandering too far away and keeps us centered in the here and now. It provides a sense of grounding, from which we may open up to the wholeness of the great expanse. With mindfulness, we also come to terms with the psychosomatic body, that is, the way we conceive the body. Do we actually understand what the body entails? This is a question that is answered by mindfulness and clear comprehension.

III. Mindfulness of the Body

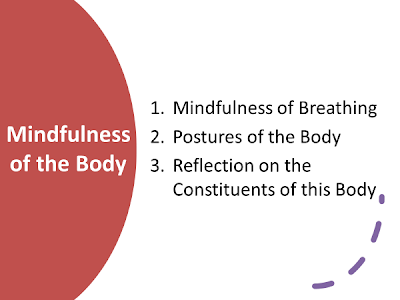

The three methods of developing mindfulness of the body are: mindfulness of the breath, mindfulness of bodily postures, and mindfulness of the constituents of the body.

i. Mindfulness of Breathing

Mindfulness of breathing has been covered in detail during session 3. It is the mindfulness of the different aspects of the in and out breath. In the event one gets lost in their practice of the other bases of mindfulness, it is best to return to breathing.

ii. Postures of the Body

After establishing mindfulness of breath, we extend mindfulness to all postures and actions in our daily lives. The four basic postures are walking, standing, sitting and lying down. The way to practice is to, in or everyday lives, be mindful of the way be physically carry ourselves. Whether we are walking around, having a shower, sitting in a chair, eating, or just getting by our day, we are ever mindful of the posture of the body. This alertness will become sharper over time, so that even subtle bodily movements are noticed. Over time, the psychosomatic body becomes ever more so present in the moment.

iii. Reflection on the Constituents of this Body

Going further, we see the body as a collection of constituents by body scanning. We start either from the soles of the feet and work our way up or start from the crown of the head and work our way down. As the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutra puts it:

“In this body there are head hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, pleura, spleen, lungs, large intestines, small intestines, gorge, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, skin-oil, saliva, mucus, fluid in the joints, urine.”

This helps us to see “the body as body”, not as “my” body or as myself, but simply as a physical form like all other physical forms. In all fairness, what part of the body represents “us”? The skin? the face? The lungs? The head? After placing mindfulness on the body in this way, we gain a psychosomatic understanding of oneself free from the vices of the ego.

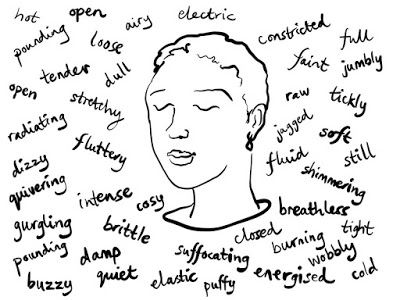

IV. Mindfulness of Sensations

Mindfulness of Sensations here refers to that of the 2nd Aggregate. Sensations can be classified in several ways: pleasant, neutral, and unpleasant. We are mindful that contact with sense objects of sight, sound, smell, taste, touch and thought produces either one of the sensations. Without discerning, we acknowledge it’s coming and going, without the “like” or “dislike” factor. For example, when we touch boiling water, that momentary sensation of unpleasantness arises. We just need to be mindful of it. When the burning sensation subsides, we also become mindful of that. This can be practiced at all times, building on the mindfulness of posture and action.

Mindfulness of sensation allows one to understand the natural responses of the human condition based on survival instincts, bodily needs, and human ecology. The constant effort for survival is regarded as a good frame of reference for mindfulness. Whenever the survival instinct functions, it produces a sense of having already survived.

Mindfulness becomes a basic acknowledgment of temporarily existing, and is an objective, impartial sense of conventional existence. As purely the product of the 2nd aggregate, we observe that sensations themselves do not present too much of an issue, and as thus, they do not need to be actively counteracted. They are, essentially, our survival mechanism.

From the perspective of developing mindfulness, of the three sensations, pleasant and unpleasant are apparent. However, neutral sensations are more subtle, and difficult to detect. When neutral sensations arise, whether we develop an unwholesome tendency towards neutral sensations, often goes undetected. As such, we are incessantly ignorant of them. Examples of the causes of neutral sensations include normal breathing, or other states neither pleasant nor unpleasant.

If we develop a firm foundation in mindfulness of sensation, it is less likely that our latent tendencies towards greed in pleasant sensations, latent tendencies towards aversion in painful sensations, and the latent tendencies towards delusion in neutral sensations have the opportunity to manifest.

V. Mindfulness of the Mind (State of Consciousness)

As for developing mindfulness of the mind or state of consciousness, we become attentive to the present state of mind, that is, to the presence and absence of the varying degrees of unwholesome states of greed, anger, delusion, the contraction of mind, distraction, and the undeveloped state of mind, as well as the presence or absence of the opposite wholesome states.

Unwholesome states are more straightforward. However, the wholesome states of non-greed, non-anger, and non-delusion are more difficult to understand. Non-greed refers to generosity, selflessness, and renunciation. Objective awareness of the presence of non-greed can be a cause for its growth, as it resonates with our innate qualities of our inner Śīla or Buddha nature.

The same is true for non-aversion, which means both loving-kindness and compassion. Loving-kindness (metta) is a universal love for sentient beings which is unconditional and selfless. Compassion (karuna), an empathy for others’ suffering and the urge to actively help them is developed on the foundation of loving-kindness. The Buddha reminds that loving-kindness and compassion are most essential for the meditator since they lead to the developing of wholesome mental states.

For a beginner, by virtue of giving rise to mindfulness of one’s negative state of mind, that state of mind cannot continue to arise, since the state of mind based on mindfulness takes place. It is perhaps important to note that consciousness arises at every instance of sense contact, which arises and ceases at lightning speed. Thus, sustained practice of mindfulness is necessary to take effect.

VI. Conclusion

For example, if we notice ourselves giving rise to the unwholesome tendency of greed as we see ice-cream, we give rise to the wholesome state of mindfulness of this greed. When we are mindful of greed, this in and of itself is considered a wholesome state, and unwholesome states cannot co-exist with wholesome states. As soon as we stop being mindful, our tendency of greed towards ice-cream may get the better of us and entertain itself by inspiring us to act out and eat the ice-cream. Such mindfulness plays a role in morality, as it offers us a choice to refrain from acting out. As we continue with this practice, gradually, our mindfulness becomes subtle to the point where we are just mindful of the arising and ceasing of such states of mind without effort.

Presence of delusion means that one has mental confusion, ignorance, and mental blindness. It means that one sees impermanence as permanence, dissatisfaction as satisfaction, and non-self as self. For example, when things start to change, one becomes perturbed, especially when one loses an object of desire or is in the company of the despised. One is unaware that things are actually changing all the time, and demands that things remain the same, though that never happens. One sees entertaining desires as satisfaction, however, in the long run, they are innately dissatisfactory, as they give rise to unwholesome mental states which inevitably lead to suffering. The presence of non-delusion means that one understands the truth of impermanence, dissatisfaction, and non-self or emptiness.

Subtler states include the contracted mind referring to the mental state of blur or stagnation. Distraction refers to the mind that is scattered, restless, and jumps around like a monkey, while the undeveloped mind refers to a weak, fearful mind easily influenced by circumstances. A great mind refers to that of the Bodhisattva who gives rise to bodhicitta, the mind of aspiration for enlightenment for the sake of sentient beings. Likewise, the awareness of the presence and absence of these states suffice. In short, mindfulness of unwholesome states of mind quietens them, while mindfulness of wholesome states of mind encourages it’s development.

VI. Mindfulness of Dharmas (Looking at mental events through the lens of the Buddha Dharma)

The fourth foundation of mindfulness requires acute yet gentle attention on the fleeting mental events (dharmas), based on the Buddhist frameworks of the five aggregates and five hindrances. Such frameworks are not to be intellectualized during mindfulness practice, rather pondered upon during one’s daily life so that one develops understanding of them. Come time to practicing the mindfulness of dharmas, one may naturally understand how they function in one’s own subjective experience. As for this foundation of mindfulness, one’s mind needs to already be in a very calm state for effective mindfulness to emerge. As such, most meditators do this after settling the mind with śamatha meditation.

The purpose of mindfulness of mental events is to see exactly what leads to dissatisfaction versus what leads to joy and liberation. We are then empowered to renounce that which leads to dissatisfaction and cultivate what leads to joy and liberation. It addresses the aggregate of volition.

In furthering our effort to understand the process of the subjective experience so as to better understand how to address afflictions and develop wisdom, we apply mindfulness to the interplay of the five aggregates.

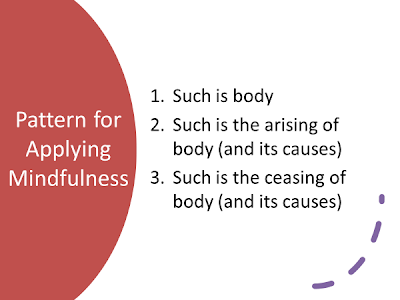

One may apply mindfulness with the pattern:

(i) such is body

(ii) such is the arising of body (and its causes)

(iii) such is the ceasing of body (and its causes)

Remember that body here refers to the six faculties and their respective sense-objects. The same pattern is repeated for sensation, perception, volition, consciousness.

It is important to remember that each moment of existence is brief, even briefer than a strike of lightning. The reason why we think that existence is continuous is due to our lack of understanding of impermanence. For instance, our body in the present moment is different from what it was a millisecond ago, since the cells have undergone many changes. Every time your heart beats, and every breath you take, your body is changed.

Once we develop mindfulness of the five aggregates, we may continue to contemplate the impermanence, dissatisfaction and non-self of each instance of the aggregates as we experience sense-contact. Dissatisfaction here refers to the fact that everything to do with the five aggregates cannot be taken as a refuge of joy and cannot satisfy us, since they are ever changing. Non-self refers to the inherent lack of autonomy of all phenomena and beings. For example, we cannot choose how long we live, and inanimate objects cannot decide what they become. Slowly and with sustained practice, we see that all phenomena only conventionally exists with causes and conditions, and become less bothered by the transient nature of life, rather, we embrace impermanence as hope for change, dissatisfaction as motivation for compassion and non-self as the potentiality of transforming unwholesomeness into wholesomeness.

VIII. Addressing the Five Hindrances: The art of self-diagnosis and prescription

During advanced stages of mindfulness practice, one may encounter certain spiritual obstacles. They may be represented by the Five Hindrances of sensual desire, ill-will, lethargy and drowsiness, restlessness and worry, and skeptical doubt prevent the attainment of deep meditation states and the arising of wisdom in everyday life.

A simile illustrates the effects of the five hindrances. As we observe our own refection in pool of water, sensual desires are like a multi-colored water surface where we cannot see own reflection. Ill-will is like boiling water, with bubbles breaking at the surface of the water, while sloth and torpor is like water overgrown with moss. Worry and restlessness are like ripples on the water surface, while skeptical doubt is like muddy, murky water. In the above situations, one cannot see one’s true self, likewise, one cannot see things as they really are. We wear the spectacles of delusion.

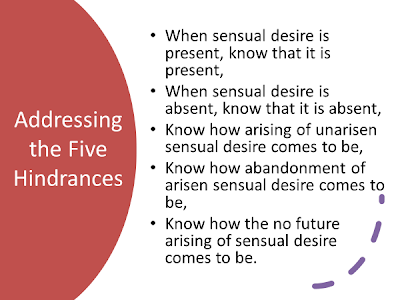

To overcome these, one may apply mindfulness with the pattern:

(i) when sensual desire is present, know that it is present,

(ii) when sensual desire is absent, know that it is absent,

(iii) know how arising of unarisen sensual desire comes to be,

(iv) know how abandonment of arisen sensual desire comes to be,

(v) know how the no future arising of sensual desire comes to be.

The same pattern is repeated for ill-will, lethargy and drowsiness, restlessness and worry, and skeptical doubt.

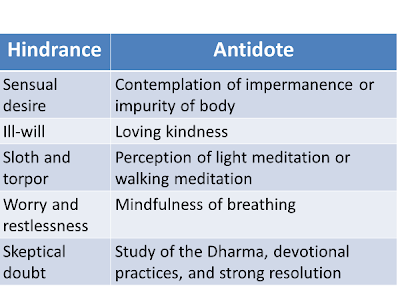

Sensual desires may be counteracted with contemplation of impermanence or impurity of body. Ill-will may be addressed with develop loving kindness. Sloth and torpor may be dealt with using perception of light meditation or walking meditation. Worry and restlessness may be settled with mindfulness of breathing. Skeptical doubt may be overcome with the study of the Dharma, devotional practices, and strong resolution.

At the first, such mindfulness is accompanied by the mental thinking of the pattern of investigation as well as the labeling of the hindrances, though over time, as one becomes familiar with them, less mental effort is needed. After self-diagnosing one’s hindrances with mindfulness, one may choose to engage in the antidotal practices to address them.

Over time, one becomes thoroughly aware of the hindrances themselves, and of their absence. One will become aware of the types of thoughts and stimuli that set off the arising process. On may also become indirectly aware of the effort required to counteract the hindrances, as well as the methods that should be used.

Here, the mindful analysis of the Five Hindrances can be likened to the work of a doctor. With the meditator being the doctor, the first course of action is to diagnose the illness of the mind, that is, to examine its symptoms and to identify its cause. The second course of action is to provide a prognosis of the extent of the illness, and the third course of action is to devise a treatment plan which includes prescription of the right medicine as well as a relapse prevention plan.

IX. Conclusion

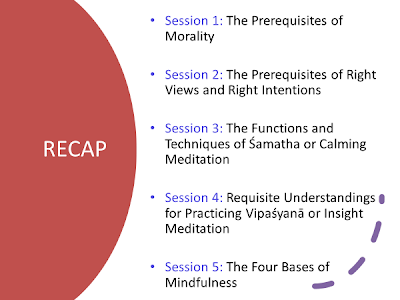

To wrap up this mini-series on Buddhist meditation, we may recall that Buddhist meditation was developed based on the Buddha’s insight into the human condition and has the goal of leading one to Enlightenment.

In other words, it has the goal of acknowledging and eliminating mental afflictions and ignorance, so that one may see the world clearly and as it is, through the eyes of prajñā wisdom. It allows one to live in this world but not be bothered by it, and intricately engaged with its affairs but not be caught up in them.

However, successful meditation is dependent on certain prerequisites. Meditation should not be viewed as an isolated practice that can stand on its own. To be effective, meditation must be practiced along with morality and wisdom, which together make up the Threefold Training.

Without a firm moral foundation, meditation is impeded by incompatible motives and a sense of guilt and restlessness. Without the guidance of right views and vows, meditation is blind, and will never produce the wonderful results it should. Without wisdom, even if one’s meditation produces good physical and emotional results, one will not find lasting joy and freedom from delusions found in one’s insight into selflessness, nor will one have the clarity and capacity of mind to altruistically benefit myriad beings.

Śamatha works to calm the mind in preparation for vipaśyanā, which develops clear insight into the reality of phenomena by mindfulness of one’s subjective world experience. Most importantly, meditation is not confined to the meditation cushion, rather, it is an attitude of life to be maintained at all times.

Thank you for joining us for session 5 (the final session) of the mini-series on meditation. If you find this Dharma service beneficial to your practice, please subscribe to the FGS English Dharma Services YouTube Channel and share it with your friends. May the merits of this session bless you with the conditions conducive of right meditation and wisdom. Feel free to tune in next week for more Dharma talks by amazing speakers from around the world! Omituofo.