Speaker: Venerable You Lu

Fo Guang Shan Buddha Musuem

I. Introduction

Hi everyone, thank you for tuning in to English Dharma Services. Today, I will continue with The Story of Purna. Last week, I talked about the birth and upbringing of Purna, and his voyages across the ocean in pursuit of wealth. When Purna went out to sea with 500 merchants for the seventh time, he came across the name “Buddha” for the first time, and that encounter gave rise to a mind of renunciation.

When he returned home, his brother Bhavila suggested that he should settle down and start a family, but Purna replied that he was not interested in marriage, and that he intended to go forth on the homeless life. His brother eventually gave Purna the permission he needed, and Purna set sail for Sravasti, taking a servant with him. In due course he arrived there.

II. Purna’s Renunciation

In Sravasti, Purna found shelter in a park before dispatching a messenger to the householder Anathapindika. The messenger went and said to Anathapindika, “Householder, Purna, the caravan-leader Purna wishes to see you.”

The householder Anathapindada thought Purna wanted to trade with him. He asked the messenger what trade-goods Purna had brought, and the messenger replied that Purna had only arrived with his servant.

Anathapindika invited him into the house and offered Purna a shower, a massage, and a meal. The two men sat and talked freely. Purna told Anathapindika that he wanted to become a bhiksu. Anathapindika sat up straight and sang in praise of his decision. Then Anathapindika took Purna to see the Buddha.

The Buddha was, at that time, giving a Dharma talk to an assembly of several hundred bhiksus when he saw Anathapindika and Purna approaching him. Seeing this, he addressed the assembly saying, “The householder Anathapindika comes bearing a gift. For the Tathagata, there is no gift equal to the gift of one who desires to undertake religious training.”

During the Buddha’s time, people made a lot of different offerings to the Buddha. What he valued most, though, was any person’s desire to take on the spiritual journey. That makes a lot of sense, because the Buddhist path begins with the Desire to embark on a spiritual journey, and one who was keen to do so, especially during the Buddha’s time, was very likely to attain Arhatship in due course. Such a person not only instills faith in others, he also aids the Buddha in spreading the teachings and helps more people embark on the path.

Anathapindika then sought the Buddha’s permission to ordain Purna into monastic life, to which the Buddha indicated his consent by remaining silence. The saying, Silence means consent, probably originated in India. The Buddha then called out to Purna, saying, “Come, bhiksu, practice the religious life.” As soon as the Buddha had uttered these words, Purna was transformed: he stood there with the appearance of a bhiksu of a hundred years’ standing, his hair and beard shaved as if done so a week ago, his body dressed in monastic robes, and his hands holding a monk’s bowl and a water-pot.

We read about descriptions of such dramatic transformations in the sutra, which illustrates the miraculous powers of the Buddha, as well as the auspiciousness of renunciation. Even Superman needs a telephone booth to transform into his superhero gear – of course, it depends on which version of the movie you are watching – but you can imagine how amazing it must be to witness a scene like this.

The Chinese Version of Purna’s Renunciation

However, the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish had a different story:

Purna went to Sravasti with 500 other merchants, who all became monastics. When the Buddha expounded the Dharma, the 500 monastics, who had previously been merchants, gained realizations and attained arhatship. Purna, on the other hand, was bonded by heavy karmic hindrance and was not able to gain a good grasp of the Buddha’s teachings. He attained the first fruit of liberation, and began to practice diligently without rest.

Sometime later, Purna paid a visit to the Buddha and asked him, “May the Lord concisely expound the Dharma upon me in such a way that, after having heard from the Lord, the Dharma thus concisely expounded, I may abide, free of desire, ardent and attentive with my senses restrained.

“The goal for which sons of good families cut off their hair and beard, don the yellow robe and with right faith go forth from the home into homelessness – may I, in this very life, realize that supreme end of religious life; may I perceive it directly; and having attained realization, may I go forth so that for me, rebirth will be exhausted, having thus accomplished the course of religious life; so that what is to be done will have been done, and I will know no birth beyond this one.”

The question that Purna raised to the Buddha was straightforward. He had a very clear goal in mind and that was; to attain liberation, so he asked the Buddha how to do so in the most direct manner.

“Therefore, Purna, listen attentively and bear in mind, what I shall tell you.” said the Buddha.

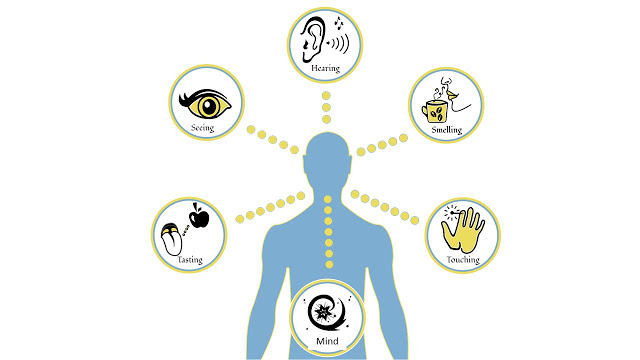

“There are, Purna, forms cognizable by the eye, sounds cognizable by the ear, smells cognizable by the nose, flavors cognizable by the tongue, tactile objects cognizable by the body, elements cognizable by the mind, all of which are desirable, agreeable, dear, captivating, delightful and connected with pleasure. And if a bhiksu, seeing such forms, delights in them, welcomes them, and in so clinging becomes dependent upon them, as a result of delighting in, welcoming, clinging to and in so clinging becoming dependent upon them, he experiences pleasure. Where there is delight in pleasure, passion arises. Where there is passion for pleasure, bondage to delight in pleasure arises. Purna, a bhiksu characterized by bondage for delight in pleasure is said to be far from Nirvana.

“But a bhiksu who has been cleansed of bondage to delight in pleasure is said to be close to Nirvana.”

“In this way, Purna, I have directed you by means of this concise exposition.”

This account of Purna consulting the Buddha for a concise Dharma instruction is missing in the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish, but I found a parallel text in the Saṃyutta Nikāya, so if we want to make sense of what actually happened, Purna could have sought instruction from the Buddha after he attained the first fruit and his other 500 companions attained arhatship. And so the Buddha gave a concise teaching of how Purna should practice with regards to his six senses, and the Buddha could have pointed this out as something that Purna needed to work on in order to attain nirvana.

In this teaching, the Buddha taught how one should not be attached to one’s sensory perceptions.

In the book Being Good, Venerable Master has once quoted the Avatamsaka Sutra which says, “The mind is the controller of everything.” In order to properly control body and speech, we must come to understand our minds. If we can control our minds, we can do anything.

Venerable Master also quoted Master Xingkong (性空; 780-862) who wrote a wonderful passage that expresses this point very well. He said, “The practice of Buddhism can be compared to presiding over a walled city; during the day, thieves and bandits must be kept at bay while at night one must be constantly alert. If the mind in charge is thoughtful and able, then there will be peace without the use of weapons.”

In Master Xingkong’s metaphor the city is the virtuous mind while the bandits are the six senses that are constantly trying to steal our peace and wisdom.

Venerable Master commented that we must have many tools in our chest when we decide to truly gain control of our minds. Sometimes we must restrict ourselves severely, and sometimes we must allow our thoughts to soar on the wings of inspiration.

In the Heart Sutra, there is a similar teaching on the six senses, whereby Avalokitesvara told Sariputra that the six senses are empty by nature, and thus there is no inherently existing eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, or mind. The objects perceived by the six senses are also empty, and thus there is no inherently existing form, sound, smell, taste, touch or dharmas. And the six forms of consciousness, from the eye consciousness unto the mind consciousness do not exist independently on their own.

In the book Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple, Venerable Master Hsing Yun talks about how we can further use our six senses to cultivate the mind, he says,

“Cultivation is definitely not about passively keeping one’s eyes, ears, and mouth to oneself. Instead, one must truly cultivate and practice. For example, not only should the eyes be prevented from looking around aimlessly, one should also look to transform adversity into conditions that help one grow. Not only should the ears be stopped from listening to unwholesome things, one should also transform frivolous speech that was heard into words of self-improvement. Not only should the mouth be stopped from speaking unwholesome words, one should also praise and encourage others with wholesome and encouraging words. When one truly cultivates the six senses, one thus practices the right path in the human world.”

This is an important attitude that is adopted in Humanistic Buddhism, for we are not merely preventing ourselves from indulging in sensual pleasure, we also understand the empty nature of the six senses and further make use of them to benefit others.

The next part of the story is what we are most familiar with—the dialogue between the Buddha and Purna in going to Sronaparantaka to expound the teachings.

“Venerable, in this way the Lord has directed me by means of this concise exposition. Now, I wish to live among the people of Sronaparantaka; I wish to make my home among those people of Sronaparantaka.”

“Purna, the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka are cruel, violent, uncouth, abusive, wrathful and contemptuous. Purna, if the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka assail, abuse and revile you face-to-face with evil, false and abusive speech, what will you think?”

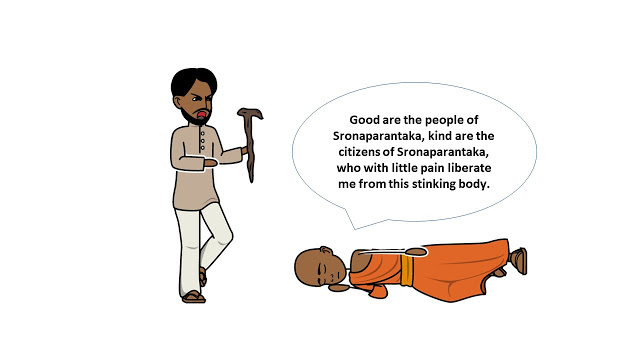

“Venerable, if the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka assail, abuse and revile me face-to-face with evil, false and abusive speech, then I shall think thus: ‘Good are the people of Sronaparantaka, kind are the citizens of Sronaparantaka, who face-to-face assail, abuse and revile me with evil, false and abusive speech, but who do not strike me with their fists or with clods of earth’.”

“Purna, the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka are cruel, violent, uncouth, abusive, wrathful and contemptuous. If the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka strike you with their fists or with clods of earth, what will you think?’

“Venerable, if the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka strike me with their fists or with clods of earth, I shall think thus:

‘Good are the people of Sronaparantaka, kind are the citizens of Sronaparantaka, who strike me with their fists or with clods of earth, but who do not attack me with clubs or swords’.”

“Purna, the people of Sronaparantaka are cruel, violent, uncouth, abusive, wrathful and contemptuous. If the people of Sronaparantaka attack you with swords or clubs, what will you think?”

“Venerable, if the people of Sronaparantaka attack me with swords or clubs, I shall think thus: ‘Good are the people of Sronaparantaka, kind are the citizens of Sronaparantaka, who attack me with swords or clubs, but who do not deprive me utterly of life’.”

“Purna, the people of Sronaparantaka are cruel, violent, uncouth, abusive, wrathful and contemptuous. If the people of Sronaparantaka deprive you utterly of life, what will you think?”

“Venerable, if the people of Sronaparantaka deprive me utterly of life, I shall think thus; “The Lord has disciples who are so exceedingly ashamed, being afflicted by this stinking body, that they even wield a knife against themselves, eat poison, kill themselves by hanging or by flinging themselves off a cliff. Good are the people of Sronaparantaka, kind are the citizens of Sronaparantaka, who with little pain liberate me from this stinking body’.”

“Well-said, Purna, well-said! With your gentle forbearance, you are quite capable of living among the inhabitants of Sronaparantaka, quite able to make your home among the people of Sronaparantaka. Go then, Purna! Having attained liberation, liberate others! Having crossed over, convey others across! Having attained calm, calm others! Having attained final emancipation, emancipate others!”.

Then, assenting to and rejoicing at the words of the Buddha, the Purna touched his head to the Buddha’s feet and departed.

From the above, we can see that Purna was a humanistic practitioner, for he chose to teach and propagate the Dharma to others. And what is so admirable about Purna was that he had chosen to go to a place where not many had wanted to go to. And this reminds us of Venerable Master Hsing Yun who had chosen to teach in Yilan in northeastern Taiwan in the 1950s because at that time, Ilan was considered to be poor and remote. Travel to Yilan from Taipei required crossing Taiwan’s central mountain range on twisting, often dangerous roads. After one visit, most Dharma teachers would never return.

Understanding Yilan’s unique situation, Venerable Master Hsing Yun decided to stay and offer his services as a Dharma teacher. Touring the temple for the first time, Venerable Master could see why no other Dharma teacher had been willing to stay. Inside, Venerable Master found three families using the temple as their home; the cushions for kneeling were missing because they had been turned into pillows for sleeping. And clothing and shoes were scattered everywhere! An elderly nun was chanting sutras in the corner when she saw Venerable Master and asked him if he was the monk coming to give the Dharma talk. When Venerable Master replied, “Yes, I am!” the nun quickly scurried away only to return thirty minutes later with a cup of tea that had already grown cold.

Soon Venerable Master was visiting on a regular basis, offering Dharma talks that met with a lot of enthusiasm. The nun was touched by Venerable Master being willing to teach in Yilan so regularly and apologized to him for her cold attitude when he first arrived, and she thanked him on behalf of all the local Buddhists. But Venerable Master did not take her cold attitude to heart and decided to stay in Yilan to teach.

So both Purna and Venerable Master Hsing Yun share the spirit of a Dharma practitioner, willing to go the extra mile to propagate the Dharma. In fact, Yilan became the cradle of Humanistic Buddhism and Venerable Master nurtured several local talents who helped spread Humanistic Buddhism even further. In 1953, Venerable Master composed a series of songs. One of them is the “Song of the Dharma Propagator,” in which he wrote:

The silvery galaxy hangs high in the sky,The bright moon illuminates the hearts,Insects and bugs chirp in the wild,Sentient beings dream deluded thoughts.

O, Buddha!Please bestow your blessings unto me,May I benefit Buddhism and all sentient beings with joy.Purna came across barbarians in his endeavors to promote the Dharma,But he was willing to sacrifice his life,Only so that Buddhism can thrive.

And this has become one of the theme songs at Fo Guang Shan!

The next day, Purna made his way to Sronaparantaka and in due course reached the kingdom. Then, having donned his robes, Purna took his bowl and entered Sronaparantaka for alms.

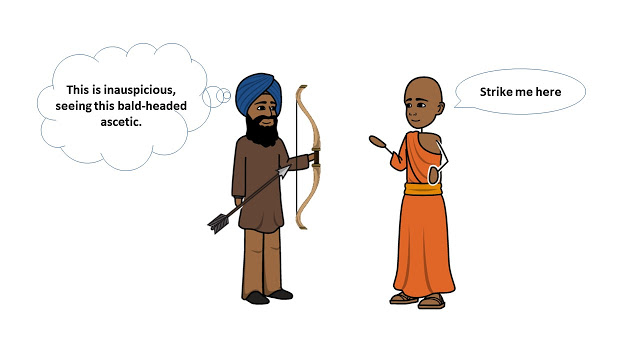

Meanwhile, a hunter approached, bow in hand, looking for deer. He caught sight of Purna and thought: “This is inauspicious, seeing this bald-headed ascetic.” Knowing this, he brought his bow to his ear and rushed at Purna. Seeing him, Purna lifted up his upper garment and said: “Good sir, I have come here for the sake of this wretched one that never gets enough, Strike me here.” And he recited this verse:

“For the sake of animals which are caught in snares, birds caught in thickets and men bearing mighty spears and arrows who are forever being killed in war;

For the sake of the wretched, miserable fish which dwell in darkness and are caught on hooks; it is for the sake of this belly that I have come from afar to this cess-pool of wickedness.”

Will Purna be killed by the hunter? We will find out next week!

Thank you again for tuning in to English Dharma Services. If you haven’t subscribed to this channel, please subscribe and hit the bell button so you would be notified on the latest updates. Goodnight and see you next week!

Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple 1

In today’s Buddhist sphere, numerous claims have been made on what the Buddha has taught. However, were they truly spoken by the Buddha? The Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple series is an exploration of over 300 topics, where Venerable Master Hsing Yun clarifies the Buddha’s teachings in a way that is accessible and relevant to modern readers. Erroneous Buddhist views should be corrected, the true meaning of the Dharma must be preserved in order to hold true to the original intents of the Buddha.

Translated & Published by: Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Read it here

Being Good

Being Good invites readers to consider what it means to lead a good life. In this collection of essays, Venerable Master Hsing Yun offers practical advice on specific moral and ethical issues, using passages from the Buddhist scriptures as a point of departure for his discussions. Topics include controlling the body and speech, overcoming greed, ending anger, getting along with others, and more.

Click here for more info.

Translated by: Tom Graham

Published by: Buddha’s Light Publications