Speaker: Venerable You Lu

Fo Guang Shan Buddha Musuem

I. Introduction

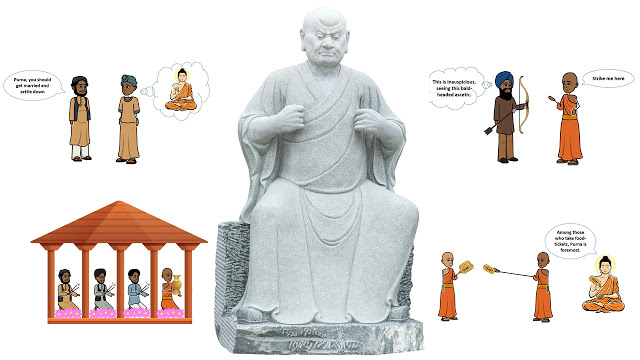

Hi everyone, thank you again for tuning in to English Dharma Services. Today we have come to the very last session of The Story of Purna. Last week, I talked about Purna’s encounter with a hunter and a brahmin in Sronaparantaka. I also talked about Purna leading his brothers in making incense offerings to the Buddha and his assembly, an incident upon which the Chinese Praise of Incense Offering is based. And we also see how Purna was foremost in accepting a meal invitation. Then the Buddha announced that bhiksus who are capable of traveling by psychic power should attend the meal invitation in Surparaka.

II. The Arrival of the Sangha

Meanwhile, the King of Suraparka had Surparaka-city swept clean of gravel, pebbles and stones, had the streets sprinkled with sandalwood-water and lined with decorated pots of various kinds of fragrant incense; had the city adorned with garlands, banners and pearls, and the roads strewn with many kinds of beautiful flowers. Surparaka had eighteen gates. The king had seventeen sons and each of the princes was stationed at a different gate. And the king himself stationed himself at the main gate, along with Purna and his three brothers.

Just then, bhiksus carrying leaves, tree-branches and water-pots began to arrive, flying in by means of their psychic powers. Seeing them, the king asked, “Venerable Purna, has the Buddha arrived?”

Purna replied, “Great King, these are bhiksus, carrying leaves, tree-branches and water-pots. The Buddha is not here yet.”

Then more venerable Elders arrived, and again the king asked, “Venerable Purna, has the Buddha arrived?”

Purna replied, “Great King, the Buddha has not yet arrived. These are the elder bhiksus.”

In the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish, the Buddha gave instructions that those with psychic power should make their way to the city of Suparaka. The next morning, Purna and his brother Bhavila were waiting to receive the Buddha and his disciples. The first person that arrived was an anagamin (one who had attained the third fruit of liberation). Bhavila asked his brother, “Is that the Buddha?”

“No,” Purna replied, “He is the cook at Jetavana and he is here to help prepare the meal.”

The next to arrive were sixteen novices headed by Cunda, and again Bhavila asked Purna, “Is that the Buddha?”

“No,” Purna replied, “Cunda is a fellow disciple of the Buddha, and he attained arhatship at the age of seven.”

The next person who arrived was an elderly monk, and seeing him, Bhavila asked, “Is that the Buddha?”

“No,” Purna replied, “That is Kauṇḍinya, he was one of the first five disciples of the Buddha.”

The next person was Mahakasyapa, whom Purna introduced to Bhavila as one who practices asceticism.

The next person was Sariputra, whom Purna introduced to Bhavila as one with great wisdom.

Following those, Purna introduced Bhavila to Mahamaudgalyayana, foremost in psychic powers; Aniruddha, foremost in supernatural vision; Nanda, the cousin of the Buddha; Subhuti, foremost in understanding emptiness; Upali, foremost in upholding precepts; Sronakotivimsa, foremost in diligence; Rahula, the Buddha’s son, and 500 other disciples who had all arrived using their psychic power.

III. The Arrival of the Buddha

In the next part of the story, both the Purnavadana and the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish have very similar narrative.

Then, outside the vihara, the Buddha washed his feet, assumed an upright posture, established himself in mindfulness, and sat down on the seat that had been especially prepared for him. As soon as the Buddha set foot in the chamber, the earth shook in six different ways.

The king asked, “Venerable Purna, what is going on?”

Purna replied, “Great King, when the Buddha sets foot on the seat with full mindfulness, he causes the earth to shake in six different ways.”

Then, from his body, the Buddha radiated golden light by which all of India became illuminated.

And once again, the king, his eyes wide with astonishment, asked, “Venerable Purna, what is going on?”

He replied, “Great King, the Buddha is radiating golden light.”

Then the Buddha, with senses restrained, set out in the direction of Surparaka accompanied by five hundred arhats.

Very soon, the Buddha reached the city of Surparaka, and he thought: If I enter by one particular gate, those at the other gates will be deprived. Suppose, then, I enter the city simply by using psychic power. And so, exercising his psychic powers, he descended from the sky right into the middle of Surparaka-city. Thereupon the king of Surparaka, Purna and his three brothers, and the king’s seventeen sons, together with all their attendants, approached the Buddha, as did many hundreds of thousands of living beings.

The Buddha, followed by those many hundreds of thousands of living beings, approached the Pavilion. Having thus approached, in the presence of the community of bhiksus, the Buddha sat down on the seat that had been especially provided.

A great mass of people, unable to see the Lord, began to force their way into the Pavilion.

The Buddha considered, “If the Pavilion is wrecked, the merit of the donors will be obstructed. I will now transform the Pavilion into crystal.” Then the Pavilion was indeed magically transformed into crystal and everyone was able to see the Buddha clearly.

After that, having arranged the required seating and the finest of foods, the three brothers informed the Buddha by messenger that everything was ready, and the Buddha took his meal.

In the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish, after the Buddha had had his meal, he gave a discourse to the entire kingdom and the family of Purna. After listening to the Buddha’s discourse, some members of Purna’s family attained the fruits of a stream-enterer, a once-returner, a nonreturner, and an arhat, and some members entered the Mahayana path. Not only that, there were innumerable people in the kingdom who, having listened to the Buddha’s discourse, attained the four fruits of liberation.

IV. The Past Life of Purna

Then, the bhiksus asked the Buddha, “Lord, what deed did Purna performas a result of which he was born into a wealthy family that possess great riches and extensive properties? And what deed did he commit as a result of which he took birth in the womb of a slave-girl and then, going forth into the homeless life, attained arhatship as a result of the abandonment of all defilements?”

The Buddha replied, “Bhiksus, the bhiksu Purna performed and accumulated many good deeds, the fruits of which were about to ripen. These exist on a multitude of levels and their effects are inevitable. Purna performed and accumulated these deeds. Who else could experience their effects? Bhiksus, those deeds performed and accumulated by Purna bear their fruit, not in the earth-element or in the water-element, nor in the fire-element or the air-element. Rather deeds that are performed and accumulated bear their fruit in the skandhas, in the psychic characteristics and in the sense-organs, where they were performed, and this fruit may be wholesome or unwholesome.

“The outcome of our actions is never destroyed, even after a hundred kalpas. And in due time and under the right circumstances, they inevitably bear fruit among living beings.

“Formerly, bhiksus, in the Bhadrakalpa, when people had a life-span of twenty thousand years, there arose in the world a perfectly enlightened one named Kasyapa, endowed with wisdom and virtuous conduct, a Tathagata, unexcelled in his knowledge of the world, a guide for those needing restraint, a teacher of gods and men. Kasyapa Buddha was staying near the city of Varanasi. Purna went forth into homelessness under his tutelage. He rendered service to the Dharma and to the Collection of the Three Baskets.

Another disciple, assigned with the job of the groundskeeper, was sweeping the vihara. The sweepings were blown up and down by the wind. He thought, ‘Let me wait until the wind dies down.’

“Meanwhile, Purna noticed that the vihara remained undeterred by the groundskeeper. Completely overcome with rage, he committed the deed of harsh speech, saying, ‘Whose slave-girl’s son is this groundskeeper?’

“The arhat heard him and thought, ‘That bhiksu is overcome with rage. Let me wait awhile. I shall inform him later.’

“When Purna’s fit of rage had passed, the groundskeeper approached Purna and said, ‘Do you know who I am?’

“Purna replied: ‘I know that you, like myself, have gone forth into the homeless life under the tutelage of the perfectly enlightened one, Kasyapa.’

“The arhat said: ‘That may be so, but since I went forth I have practiced the spiritual life just as it should be practiced and have been liberated from bondage. On the other hand, you have committed the deed of harsh speech. Therefore confess the offense. In this way, the offense will be a small one and will be removed and completely exhausted.’

“And Purna confessed the offense.

“Now Purna was to be reborn in hell and thereafter as the son of a slave-girl but, because he had confessed, he was not reborn in hell. However, for five hundred births he took rebirth in the womb of a slave-girl, even in this very last birth before he was enlightened, he was born again from the womb of a slave-girl.

So here we see the importance of confession and repentance, because being regretful of what we did wrong can help lessen the implications that arise from the misdeeds we made.

However, because of his service to the monastic community, Purna was born into a wealthy family, one possessed of great riches and extensive properties. And because he read and studied and worked for the welfare of many, he went forth into homelessness under my tutelage, and as a result of freeing himself from all defilements, attained arhatship.”

In Buddhism, we often talk about the importance of accumulating wisdom and merit, so when we undertake the study of Buddhist teachings, we are accumulating wisdom. And at the same time when offer our services to others, especially in the monastic community, we are accumulating merit. By accumulating both wisdom and merit, we can gather favorable conditions not only for a better future, but also for the eventual goal of enlightenment.

The Buddha went on to say,

“Therefore, bhiksus, it is said: ‘The fruit of wholly black deeds is [itself] wholly black; the fruit of wholly white deeds is [itself] wholly white; and the fruit of mixed deeds is [itself] mixed.

“Therefore, then, bhiksus, abandon wholly black deeds as well as mixed deeds and direct your own earnest efforts toward wholly white deeds. In this way, bhiksus, should you train yourselves.”

Thus spoke the Buddha. Their hearts gladdened, the bhiksus rejoiced at the Buddha’s words.

V. The Law of Karma

And so we can see from the last part of this story that:

Firstly, deeds are never destroyed, even after a hundred kalpas. And so in every moment of our lives, we should be aware of how we act, speak, and think. In the case of Purna, although he confessed after committing harsh words, he suffered the fruits thereof for a long time.

Secondly, what you sow is what you reap. Positive and negative karmic actions have distinctive results. As the Buddha said, “

‘The fruit of wholly black deeds is [itself] wholly black; the fruit of wholly white deeds is [itself] wholly white; and the fruit of mixed deeds is [itself] mixed.

In Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple, Venerable Master Hsing Yun says:

“Most people believe that being filial to their parents brings wealth, being caring for their children brings honor, praying to the Buddha brings longevity, and being generous brings promotion. But these are distorted understandings of cause and effect. Being filial to one’s parents is ethical and moral conduct; it has nothing to do with becoming wealthy. Becoming wealthy has its own cause and effect. The causes and effects of wealth are to work hard, to have initial capital, and the ability to run a business.”

So what it means is, you don’t get an apple by planting an orange seed, nor do you get an orange tree by planting an apple seed. Each cause produces a distinctive result.

And the Buddha’s message to the bhiksus in this section, is that one should also abandon all forms of negative deeds, and train to accumulate all forms of positive deeds.

Thirdly, small actions can have serious consequences. Because of his harsh speech towards an Arhat, Purna was reborn as a child of a slave-girl for five hundred lifetimes. The weight of his karma was caused by what he had done toward an arhat. We should be extremely mindful of our actions, speech, and thoughts, because anybody we meet in our lives could be an arhat in disguise. We might think of an arhat as somebody special, but in the case of Purna, the arhat he met was a groundskeeper, so an arhat could be any ordinary person that is around us. He could be a chef, he could be an accountant, he could be a staff at the train station, we never know. We can never be sure of the spiritual attainment of others, so it is better to be respectful to everyone we meet, especially those whom we thought are inferior to us or who look younger than us.

Also in this story, we see a parallel between the Purnavadana and the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish, which means both stories could have originated from the same source, but adapted differently due to geographical and cultural circumstances. Reading parallel texts and getting different interpretations of the same story can help us to get a better overall picture. We also find the incident of making incense offering in this avadana, which goes to show that the idea of making incense offering has originated from the Buddha’s time and adapted into a practice we observe in Buddhist shrines today. We can also see how people have valued the importance of this incident that it has been remembered in the form of a praise that we chant so commonly in Buddhist liturgy.

Due to time restraints, I have left out several sections of the Purnavadana, and I urge you to read the full text if you have the time to do so. I am sure you will discover more in this precious text. If you are able to read Chinese, I suggest that you refer to the “Chapter of Funaqi (富那奇緣品)” in the Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish as published in the Fo Guang Buddhist Canon, for comparison.

VI. Conclusion

If you ever come to the Fo Guang Shan Buddha Museum, please remember to look up Purna at the Bodhi Wisdom Concourse! He is a reminder of how we should practice as a Humanistic Buddhist practitioner. We see how Purna, over many lifetimes, from the time of Kasyapa Buddha to the time of Sakyamuni Buddha, how he turned from one who is overcome with rage when he saw the unswept leaves on the ground of the vihara, to one who displays forbearance even at the verge of losing his life. So when someone makes you angry, think about Purna, how he was humiliated and how he gave rise to the perfection of patience, and how he touched the hearts of difficult people with his gentle forebearance at Sronaparantaka.

Finally, I hope you enjoyed these four sessions. May you be inspired by the deeds of Purna, and may we all aspire to propagate and spread the Dharma, like how Purna did.

Thank you again, for tuning in and if you haven’t subscribed to this channel, please remember to do so and hit the bell button so you will be notified of the latest updates. For now, goodnight!

Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple 1

In today’s Buddhist sphere, numerous claims have been made on what the Buddha has taught. However, were they truly spoken by the Buddha? The Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple series is an exploration of over 300 topics, where Venerable Master Hsing Yun clarifies the Buddha’s teachings in a way that is accessible and relevant to modern readers. Erroneous Buddhist views should be corrected, the true meaning of the Dharma must be preserved in order to hold true to the original intents of the Buddha.

Published by: Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Read it here