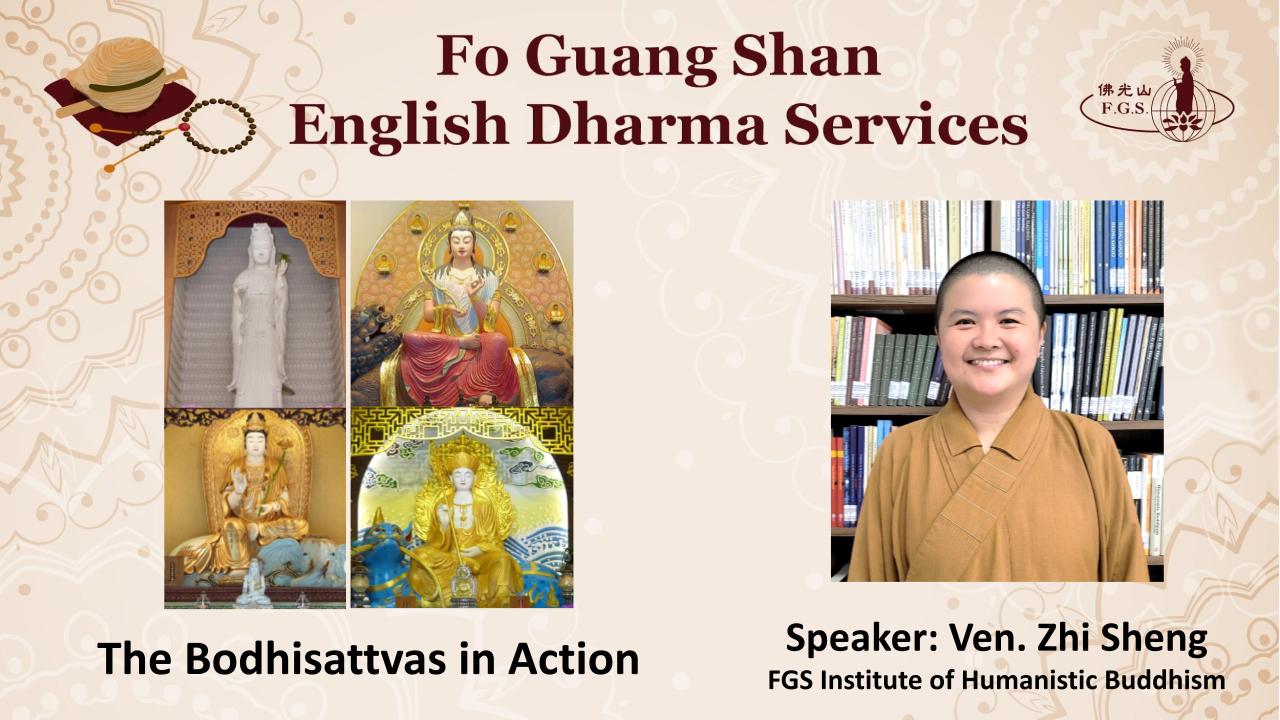

Venerable Zhi Sheng

Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

I. Introduction

Auspicious Blessings.

Welcome to the Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services. My name is Zhi Sheng from Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism.

Today, I would like to discuss the Bodhisattvas in Action from 3 perspectives:

- What does bodhisattva mean?

- Who are the Bodhisattvas?

- How does Venerable Master Hsing Yun practice as a bodhisattva?

II. Defining Bodhisattva

Let us first understand the embedded meaning of the word bodhisattva. It is a Sanskrit word made up of two parts: bodhi means awakening or enlightenment, and sattva refers to any sentient being. Thus, the term bodhisattva embodies “enlightenment and sentience,” and it means “a sentient being with the mind for the truth.”

Furthermore, there are two aspects to “enlightenment and sentience”:

First, it speaks of the commitment and dedication to seek enlightenment, in other words, one’s own efforts in the attainment of ultimate wisdom. Therefore, we also describe a bodhisattva as one who seeks the path.

Second, it speaks of the devotion to bringing enlightenment to all sentient beings, in other words, efforts for the benefit of all. This is the manifestation of compassion, and it explains why we also describe a bodhisattva as one who delivers sentient beings.

To put that simply, a bodhisattva is one who “seeks the Buddha Way and delivers all beings.”

III. The Four Great Bodhisattvas

So, who are the Bodhisattvas? When asked, most Buddhists think of the Four Great Bodhisattvas, namely, Avalokitesvara, Manjusri, Samantabhadra, and Ksitigarbha Bodhisattvas.

Let’s look at each of them briefly. Avalokitesvara is known as the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion. Avalokitesvara can be rendered as “lord who gazes down (at the world).” With great compassion, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva made the 12 great vows of helping all sentient beings cross the sea of suffering. When we call to Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva for help and guidance, Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva manifests in different forms to help us regardless of where we are.

Manjusri is known as the Bodhisattva of Great Wisdom. Manjusri means “Gentle Glory” in Sanskrit. He holds aloft the sword of wisdom and rides upon a golden lion. The sword represents the wisdom that cuts through ignorance, and the lion symbolizes the powerful energy of the lion’s roar, the teaching of the Dharma.

Ksitigarbha is known as the Bodhisattva of Great Vows. Ksitigarbha means “earth treasury,” as he is “stable and unmoving like the great earth, meditating with depth and seclusion like a secret treasury.” When Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva saw sentient beings suffering in the karmic flames of hell, he thought, “If I do not enter the gate of hell, who will?” So, he pledged, “I vow not to enter into Buddhahood until all hells are empty.” This means that Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva will defer his attainment of Buddhahood as long as there is one single being suffering in hell.

Samantabhadra is known as the Bodhisattva of Great Practice. He is one of Sakyamuni Buddha’s attendants along with Manjusri. Samantabhadra’s virtue manifests his pure magnanimity everywhere, and as such his name means universal virtue. This Bodhisattva rides on a six-tusked white elephant, which is a metaphor that Samantabhadra Bodhisattva uses the great strength of loving-kindness to practice and put the six perfections into action.

IV. Spirit of a Bodhisattva

The Four Great Bodhisattvas set good examples for us to follow through compassion, wisdom, vows, and practice. These four aspects are the spirit of bodhisattvas.

Compassion is the source of energy that provides bodhisattvas with the strength to practice the Mahayana spirit of attaining fulfillment for oneself through the fulfillment of others. It is out of compassion that the Buddha taught the Dharma for more than 40 years, and left us the numerous teachings.

Prajna-wisdom is the wisdom that allows us to see through worldly differences. It is the “non-discriminating mind,” where the clinging to the discriminating notion of self and other objects is absent. In other words, prajna-wisdom allows us to understand emptiness, that self and the universe are mutually interdependent, and all sentient beings and self are one.

Bodhisattvas use their wisdom to practice compassion, and they use their kindness to complete wisdom.

Prajna-wisdom and compassion are the two sides of a coin. There are two, yet there is one; there is one, yet there are two. Prajna-wisdom and compassion are the core of the bodhisattva principle.

Bodhisattvas do not look at sentient beings as apart from themselves. Sentient beings are their hearts and minds, and their hearts and minds are sentient beings.

To demonstrate this, I would like to refer to a story of Venerable Master Hsing Yun.

During the establishment of Fo Guang Shan Monastery, many Buddhist summer camps for college students were organized. Among them, there was one which Venerable Master said to be the most unforgettable. This happened in 1970. Yes, way before many of us were even born. On the evening of the 1st day of the camp, the water-pump motor unexpectedly broke. A technician was called in to fix it. He kept working on it until 1AM, but was unsuccessful. The technician said to Venerable Master, “I need to go and get spare parts for the motor, I’ll be back later.” Venerable Master asked the director of the monastery to go with him. When they both returned, the director said to Venerable Master, “Good thing that I went with him. He was trying to find an excuse to go to sleep.”

For the rest of the hours, Venerable Master and the director stayed with the technician while he worked. As the hours drew nearer to sunrise, still worried, Venerable Master went across the grassland and through the bamboo grove to the water tower.

As he put his ear near the tower, it sounded like running water. With doubt, he climbed up to the top of the tower, stretched his hand inside the tower, and touched the water. It was at that moment that he stopped worrying. He thought to himself, “If there were no water, I am willing to transform my blood into water. May there be running water for everyone at the monastery.”

From this story, we can see that Venerable Master’s heart and mind were focused on the benefit of others. Compassion, wisdom, vows, and practice are all embedded in Venerable Master’s actions. Out of compassion, he thought of the students and people at the monastery. His wisdom was demonstrated in how he instructed the director to go with the technician to get the spare parts. He made vows to transform his blood into water. His willingness to give parts of himself is an act of a bodhisattva.

I would like to share another example of how Venerable Master practiced as a bodhisattva.

When Fo Guang Shan was new to the area, someone would occasionally bring in an abandoned child from the street. Venerable Master felt sorry for the children and subsequently built a home and a nursery school for them.

The home is named Da Ci Children’s Home. Since 1970, the Home has raised and educated over 800 children. Many have excelled and succeeded in societies and all walks of life.

Each year during the Spring Festival, a month-long costume parade and charity sale is the most important opportunity for the children of Da Ci Children’s Home to showcase their learning and achievements throughout the year.

From this example, we can see how one bodhisattva can make a huge difference in changing the lives of many people.

Therefore, the term bodhisattva is not limited to enlightened individuals whose statues we see in temples. In fact, we address all those who are determined to embark on the Buddha path as bodhisattvas. With determination, any one of us can become a bodhisattva.

V. Conclusion

Thank you so much for listening! May you find peace and joy in the Dharma.

If you would like to listen to more content, don’t forget to subscribe to our channel, Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services.