Speaker: Ven. Zhi Tong

FGS Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Auspicious greetings to all viewers around the world! Welcome back to another episode of Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services. In this episode, we will continue from last week’s discussion on the Six Perfections.

I. Recap

Let’s refresh our memories of last week’s episode. First, we discussed four questions:

1. What is a bodhisattva?

2. Who can be a bodhisattva?

3. How to be a bodhisattva?

4. What do bodhisattva practice?

We also talked about the first of the Six Perfections, which is the Perfection of Generosity, as well as the three ways we can practice generosity, and they are:

1. Giving of wealth

2. Giving of Dharma

3. Giving of Fearlessness.

For today’s episode, we will be talking about the perfections of Precept, Patience, and Diligence.

II. Perfection of Precept

Upon hearing the word “precept,” what comes to your mind? Is it rules? Restrictions? Limitations on your actions? On the surface, it may seem that precepts are restrictions on our actions. If our actions are restricted, how can we, as bodhisattva, actively help people?

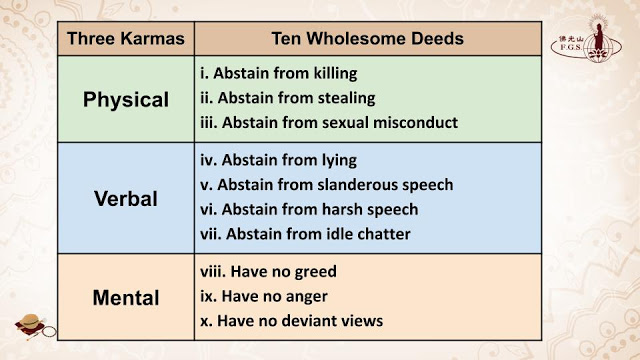

Let us first take a look at one of the fundamental precepts that bodhisattvas uphold: the Ten Wholesome Deeds. The Ten Wholesome Deeds are:

i. Abstain from killing

ii. Abstain from stealing

iii. Abstain from sexual misconduct

iv. Abstain from lying

v. Abstain from slanderous speech

vi. Abstain from harsh speech

vii. Abstain from idle chatter

viii. Having no greed

ix. Having no anger

x. Have no deviant views

Perhaps you might be turned away from the Ten Wholesome Deeds upon the first glance. It looks like a list of things we cannot do. So why don’t we break down the Ten Wholesome Deeds into three parts?

Each of the ten deeds are corresponded to one of the Three Karmas. The first three are related to our physical karma, the next four are related to our verbal karma, and the last three are related to our mental karma.

The first three of the Ten Wholesome Deeds are three of the fundamental precepts of Buddhism. The Buddhist Five Precepts also start with these three. Let’s take a look at the first deed.

i. Abstain from killing

Abstain from killing means not to harm the lives of any being. But that’s not all to this precept. Except for not harming the lives of other beings, we should also be respectful to every life. Every life is precious, no matter if it is an ant, a frog, a dog, or even a shark, and especially the lives of all human beings. Every life should be respected and taken care of. If we could do this, then we are also becoming a more kind and compassionate person.

ii. Abstain from stealing

What about abstaining from stealing? Stealing is an act of taking something that does not belong to us without permission from the owner. By abstaining from stealing, we are actually respecting people’s possessions and properties. In this way, we will slowly earn a respectable reputation.

iii. Abstain from sexual misconduct

Sexual misconduct means having an intimate relationship with people that is not your spouse or partner. In other words, extramarital affairs. By abstaining from sexual misconduct, we are not violating the body, reputation, or family of other people. More importantly, we respect the everyone around us and their family. If we could abstain from sexual misconduct, then naturally, we will also enjoy a harmonious and joyful relationship with our family members

The next four of the Ten Wholesome Deeds are related to our verbal karma.

i. Abstain from lying

First, we have abstain from lying. This is also the fourth of the Five Precepts. Abstaining from lying isn’t just about not speaking words that are untrue, but also remind ourselves to speak truthfully.

ii. Abstain from slanderous speech

Abstain from slanderous speech means not to talk in a two-faced manner that ruins people relationships. For example, Tina and Sophie are best friends, but one day their colleague Jenny told Tina that Sophie is the one who stole her lunch every day, and then went and told Sophie that Tina was the one who dented her car. Because of Jenny’s words, the two friends argued and turned against each other. The way Jenny talks is slanderous speech, with the intention of ruining people’s relationships. The intention of our speech is also very important, and it should come from a sincere mind.

iii. Abstain from harsh speech

Sometimes, the words that comes out from our mouth is harsh and cruel, intending to hurt the other person. This is why we should abstain from harsh speech and not to say or scold others with vicious words. This is also a reminder for us to speak kindly.

iv. Abstain from idle chatter

Eminent masters of the past would not take single step unless they are going to propagate the Dharma, or say a single word unless it is the teaching of the Buddha. Sometimes, we find ourselves chattering away with our friends or family about something that we will forget right after the words leave our mouths. But for some people, everything that they say seems to have weight because of the meaning that they are conveying. Therefore, abstaining from idle chatter is not only a reminder for us to say things that are meaningful, but also be aware that words have power.

Speaking is the most important way we communicate with other people, and it is very easy for us to let our tongue get the better of ourselves. This is why the Ten Wholesome Deeds remind us to speak truthfully, sincerely, kindly, and meaningfully to others, so that our words bring comfort and encouragement to people, instead of harm and injury.

The final three of the Ten Wholesome Deeds concerns our mental activities.

i. Have no greed

The first is to have no greed. In Buddhism, greed, hatred, and ignorance are known as the Three Poisons, which is the root of our afflictions and troubles. When we have no greed, we are not attached to the people and things around us. Moreover, we are content with what we have. As we slowly lessen our greed, we find that we become a more generous person.

ii. Have no anger

With anger comes the intention to harm, whether verbally or physically. When we have no anger, we have no inclination to harm any being. Naturally, we will have kindness for everyone, becoming a more compassionate practitioner.

iii. Have no deviant views

Last but not least of the Ten Wholesome Deeds is have no deviant views. In other words, we need to have right view. Have right view about the law of cause and effect, and of what is wholesome and unwholesome, so that we know how to conduct ours physical, verbal, and mental karmas righteously and wholesomely. When our actions are guided with right view, naturally we will be righteous people.

Precepts are not restrictions. In fact, precepts are our guide. For example, the Ten Wholesome Deeds are the basic guidelines for all bodhisattvas because it helps us to understand that our actions bring consequences. When we understand how our actions may affect both ourselves and others, we will know better how to conduct ourselves so that both we and other people are benefited. This is why the Ten Wholesome Deeds is the foundation of all good conduct.

As Venerable Master said in Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple,

Precepts are like a teacher that guides one through what should and should not be done.Precepts are like a rampart, keeping one safe.Precepts are like a virtuous book, increasing one’s virtues so that others feel comfortable in one’s company.Precepts are akin to the foundations in building a palace; without the protection of precepts, the twists and turns of life will be hard to tolerate.

There is no need to fear the precepts; instead, uphold them as carefully as if protecting one’s eyes. The true meaning of upholding the precepts starts from not violating others onto elevating and protecting all sentient beings.”

III. Perfection of Patience

Before I go into details about the perfection of patience, let’s take a moment and imagine this:

As you learn more and more about Buddhism, you are inspired by the great bodhisattvas and vowed to be a bodhisattva that can liberate both yourself and other sentient beings. You are ready to do whatever it takes to help people, no matter if it is giving away your possessions or spending your time and effort for a wholesome cause. But as you take your first step as a new bodhisattva, you find that sometimes your efforts are actually not appreciated by other people! Some people actually scorned at your act of giving or kindness. If this happens to you, what will you do? Will you still continue on the path as a bodhisattva?

This is where the perfection of patience comes in. There are three categories of patience, namely,

i. Tolerating hateful insults and harms

ii. Calmly tolerating suffering of all kinds

iii. Patience to observe the Buddha-Dharma carefully

i. Tolerating hateful insults and harms

No matter what we do in life, whether in our respective careers or striving to be a bodhisattva practitioner, we might face physical or mental harm. The first kind of patience is to tolerate hateful insults and harms that comes our way. When someone hurt us with harmful or even violent intentions, we practice compassion, knowing that these people are driven by afflictions and influenced by unwholesome forces.

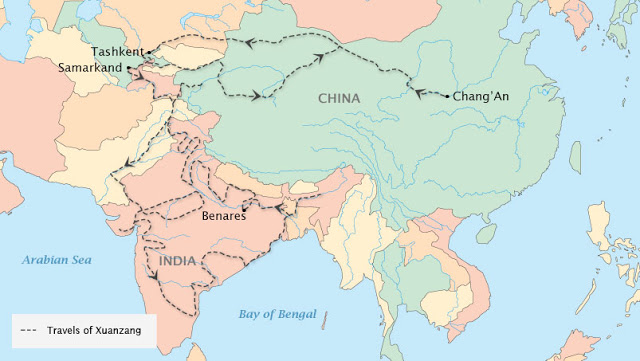

Master Xuanzang is one of the greatest Chinese Buddhist masters and translators. At the age of 27, he decided to travel to India to search for original Buddhist sutras to resolve the doubts that he found in different schools of Buddhist teachings.

At the very beginning of his travels, he acquired a guide that can help him cross the desert. But just the night before their journey into the great desert, this guide had a change of mind. He unsheathed his knife and advanced closer to Xuanzang. Perhaps he wanted to kill Master Xuanzhang, since they were travelling illegally. Perhaps he wanted to capture Xuanzang and sent him to the guards in hope to get some repayment. Master Xuanzang saw the guide’s movements. Instead of confronting the guide, he meditated and recited the name of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva. On the next day, they parted ways amicably.

Despite facing a person that almost murder him, Master Xuanzang remained calm and patient, understanding that the guard was also troubled by external circumstances. In the end, no one was hurt.

ii. Calmly Tolerating suffering of all kinds

The second kind of patience that we can practice is to calmly tolerate suffering of all kinds. Suffering can come in many forms. For example, the weather, temperature, or animals. But more importantly, when we choose to be a bodhisattva practitioner, we are faced with the sufferings that our cultivation brings.

Let’s go back to the story of Master Xuanzhuang. When he left China for India, it was a tumultuous time for China, as there was a shift in the country’s ruling power. The government decreed that no one can leave the land of China, so Master Xuanzhuang actually left the country illegally. To get to India, he had to cross great deserts and climb over snowy mountains, all alone except for an old horse as a guide. Once, he accidentally spilled his waterskin in the middle of the desert, and almost died of thirst. Despite these physical adversities and mental pressure, Xuanzhuang said, “I vow to keep on travelling West, even if it leads to my death, than taking a step back to the East, even if I will live.”

Master Xuanzang put his physical and mental sufferings aside, and he was undeterred by the harsh external conditions during his travels. This is why he could reach India successfully with nothing by his two feet and a powerful vow to seek the Dharma.

iii. Patience to observe the Buddha-Dharma carefully

Last but not least is the patience to observe the Buddha-Dharma carefully. Patience is indeed easier said than done, especially when we are hurt by others. Therefore, we need the Buddha-Dharma to help increase our patience. When we observe that all phenomena arise and cease according to causes and conditions, then we find it easier to stay calm and unaffected by the phenomena around us.

When Master Xuanzang returned to China after 16 years of travelling and studying in India, he began to translate the Buddhist texts that he brought back. One day, he saw a young man who has the intelligence and the potential to assist him in his translation project and asked if the young man if he would like to renounce and be his disciple. Of course, the young man has no inclination of becoming a monk, but he finally conceded under three conditions. The young man asked to have three carts of books, wine, and ladies to go with him wherever he went, as he couldn’t live without any of them. Though it is inappropriate for a monk to have wine and wife, Master Xuanzang agreed. He understood that this is a process the young man has to go through. And indeed, after becoming a monastic, the young man studied the sutras and helped with Master Xuanzang’s translations, and actually realized that there is more joy in the Dharma than in wine. He then truly renounced, both physically and mentally, as a monastic, and became the Master Kuiji, Master Xuanzang’s greatest disciple.

As Venerable Master Hsing Yun said in Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple,

Patience is neither passively compromising nor holding in one’s anger—it is kind and compassionate tolerance for others. Those who practice patience and compassion truly understand that all are one and equal.

Just like Master Xuanzang, with his great patience, he could travel across unimaginable distance under extreme conditions. With his great patience, Master Xuanzang saw potential in a young man and patiently helped him to find his way in the Dharma. It is because of his great patience that Master Xuanzang became one of the greatest masters in Buddhist history.

IV. Practice of Diligence

One day, a disciple by the name of Aniruddha accidentally dozed off when he was listening to the Buddha’s teaching. The Buddha reprimanded him with a verse,

“Pity! For your love of sleeping

You are like a clam

Sleeping for a thousand years

Without ever hearing the name of the Buddha.”

Aniruddha was ashamed of himself and said, “Please forgive my laziness. From today on I vow never to sleep and instead practice diligently.”

The Buddha was glad to see that Aniruddha is willing to change himself for the better, but also advise, “Cultivation cannot be accomplished if we work too hard or too little. You must cultivate accordingly.”

However, Aniruddha stuck to his vow and would not rest even for a minute. In just a few days, his body could not handle it and his eyes started to hurt. Even though the Buddha advised him again practice and rest accordingly, but Anirruddha refused to listen. Soon enough, Aniruddha went blind from over-exertion.

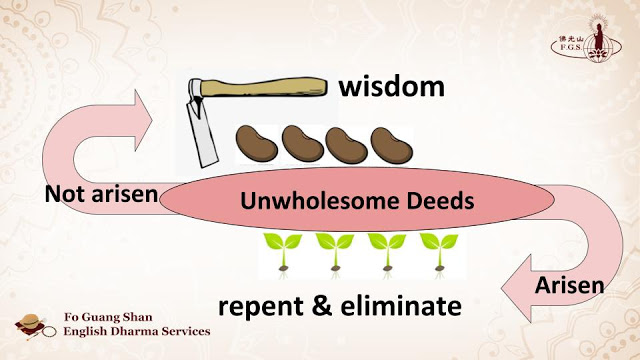

Is this what diligence is about in Buddhism? Does it mean that we have to practice tirelessly until our physical body give out to perfect the cultivation of diligence? This is not right diligence. According to the Noble Eightfold Path, the Buddha taught us four kinds of Right Effort, and they are:

i. To prevent unwholesome states that have not yet arisen.

ii. To end unwholesome states that have already arisen.

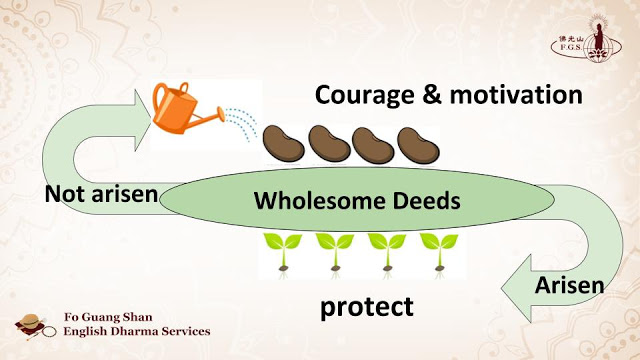

iii. To develop wholesome states that have not yet arisen.

iv. To strengthen wholesome states that have already arisen.

For unwholesome deeds and thoughts yet to arise, prevent them by using one’s wisdom.

For unwholesome deeds already committed, one should bravely repent and end them.

For wholesome deeds and thoughts yet to arise, one should develop them with courage and motivation.

For wholesome actions and thoughts already existing, one should protect them so they are enhanced. In short, one should be hardworking and diligent in preventing the unwholesome and cultivating the wholesome.

One cannot afford a moment of laziness or indolence.

Going back to the story of Aniruddha, after he became blind, even though he still continued practicing, he had troubles participating in the everyday activities with the rest of the Sangha, and sometimes he couldn’t even manage his own things. For example, he couldn’t patch his robes even when they are torn. So he had no choice but to request help from another monk. When the Buddha heard of this incident, he went to Aniruddha and helped him to sew his robes. Furthermore, the Buddha also taught Aniruddha the right way to be diligent.

Soon after, with the guidance of the Buddha, Aniruddha attained the supernatural power of divine eye that enabled him to see not just things around him, but all the Dharma realms as well.

Diligence is an indispensable practice in the Six Perfections, for this is the attitude we need to have in practicing the bodhisattva path. In other words, we need to practice the perfections of generosity, precept, patience, meditative concentration, and prajna wisdom diligently. With diligence, we can perfect our merit and wisdom.

Diligence is like the tortoise in the fable of the Tortoise and the Hare. Sprinting towards the ultimate goal will only burn us out before we reach it, and we might even lose faith and confidence in our practice. This is why we need to be like the tortoise, our pace may be a little slow, but we take each step resolutely and make no stop until we reach the goal.

V. Conclusion

Before we end today’s session, let’s recap what we discussed today.

For the Perfection of Percept, we talked about the Ten Wholesome Deeds, which are:

i. Abstain from killing

ii. Abstain from stealing

iii. Abstain from sexual misconduct

iv. Abstain from lying

v. Abstain from slanderous speech

vi. Abstain from harsh speech

vii. Abstain from idle chatter

viii. Having no greed

ix. Having no anger

x. Have no deviant views

For the Perfection of Patience, we talked about practicing patience with three steps:

i. Tolerating hateful insults and harms

ii. Calmly Tolerating suffering of all kinds

iii. Patience to Observe the Buddha-Dharma carefully

And for the Perfection of Diligence, we talked about

i. To prevent unwholesome states that have not yet arisen.

ii. To end unwholesome states that have already arisen.

iii. To develop wholesome states that have not yet arisen.

iv. To strengthen wholesome states that have already arisen.

Thank you for listening to this episode. Next week, we will be discussing the perfections of meditative concentration and prajna wisdom. May you find joy and inspiration in this Dharma talk. Omitofo.

Read more about Four Noble Truths!

Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple 1

In today’s Buddhist sphere, numerous claims have been made on what the Buddha has taught. However, were they truly spoken by the Buddha? The Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple series is an exploration of over 300 topics, where Venerable Master Hsing Yun clarifies the Buddha’s teachings in a way that is accessible and relevant to modern readers. Erroneous Buddhist views should be corrected, the true meaning of the Dharma must be preserved in order to hold true to the original intents of the Buddha.

Published by: Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Read it here