Speaker: Ven. Zhi Tong

FGS Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Auspicious greetings to viewers around the world. Welcome to a new episode of Introduction to Buddhism. This is our third and last episode on the Six Perfections. Before we begin, let’s briefly go over what was discussed in the last two episodes.

I. Recap

In the first episode, we discussed the basic definition of a bodhisattva, as well as the first perfection, the perfection of generosity. We touched upon how we can practice generosity in our daily lives.

As for the second episode, we learned about the perfections of precept, patience, and diligence.

Upholding precepts is about not violating other people and sentient beings; moreover we learn to respect them and treat them with compassion.

Patience is a practice in increasing our inner strength. It is not only about keeping one’s cool in face of internal or external adversity, but to remain kind under challenging circumstances.

As for diligence, it is a persistent effort that encourages us to do all that is wholesome. We need to be diligent when practicing all of the Six Perfections. In other words, we need to practice generosity, precept, patience, meditative concentration, and prajna wisdom diligently.

In this episode, we will be looking at the last two perfections, which are the perfections of meditative concentration and prajna wisdom.

II. Perfection of Meditative Concentration

Meditation and mindfulness are two terms that have seen an increase in popularity in the last few decades. Many people are drawn to the practice of meditation and mindfulness as a way to deal with their stress and to reconnect with themselves.

The practices of meditation and mindfulness are not specific to any religions or traditions. Buddhists have been meditating for the past 2600 years. So the question is, why do Buddhists practice meditation? What is the purpose of meditative concentration?

i. Why do Buddhists practice meditation?

The goal of Buddhist practice is to attain enlightenment. But before we can achieve this, we need to purify our physical, verbal, and mental karma, and to accumulate merit and wisdom. Meditative concentration is a way to purify our Three Karmas. As we sit in meditation, our mind is focused on a meditative object, for example, our breathing. This practice guides us back to the present moment, to be mindful, so that we will not be distracted and overwhelmed by what’s happening inside ourselves and also outside. This is a state of serene equanimity.

But what happens after our mind is calm and serene? When we are in this clear-headed state, we can contemplate upon the teachings of the Dharma and cultivate our wisdom. Gradually, we will be able to discover our intrinsic nature.

Meditative concentration helps us to clear the sediments of our minds and allow our wisdom to emerge. If we truly put our hearts into practicing meditation, you will discover the wonderful potentials that you never knew you had.

ii. How do we practice meditation?

So, how do we practice meditation? It doesn’t start with sitting down on a cushion and closing your eyes.

In the book, Xiao Zhi Guan (小止觀; Condensed Techniques for Stopping Delusion and Seeing Truth), it instructed that there are five things we need to balance as a beginner in practicing sitting meditation. They are: to have balanced meals, balanced rest, a balanced body, balanced breathing, and a balanced mind.

1. Balanced meal

What does it mean by “balanced meal?” It means to have regular meals every day, and not to overindulge or starve oneself. It is harder for us to focus on our meditation if we sit with a full or empty stomach. Moreover, eat food that is beneficial to our body, so that we have a healthy body to practice meditation.

2. Balanced rest

Secondly, to have balanced rest. Cultivation is not measured by the length of time a person does not fall asleep. If we cultivate in a sleep-deprived state, then we would spend most of our cultivation time trying to stay awake. Similarly, if we put ourselves in continuous sleep, then can we even call ourselves practitioners? If we wish to meditate well, then we should rest accordingly so that we can remain alert for our cultivation

3. Balanced body

Next, we need to balance our body. The first thing you learn about sitting meditation is correct sitting posture. We should sit with our legs crossed in half lotus or full lotus position, our backs should be upright, our hands are in the meditation gesture, our eyes closed, our chins tucked, and our tongue resting on our upper palate.

Correct sitting posture helps us to be more focused when meditating.

4. Balanced breathing

Breathing is a very important aspect in Buddhism. Usually, we are not aware of how we breathe, so we find ourselves breathing shallowly, loudly, or uncomfortably. The practice of sitting meditation helps us to be aware of our breathing, and we will find that after practicing meditation, our breath is more balanced, more deep, and more steady.

5. Balanced mind

Last but no least, to have a balanced mind. Our minds are like a wild monkey that jumps up and down without even a moment of peace. Meditation reins our monkey mind and leads us to focus on the present moment. It guides us to have a balanced mind.

These are the five things we need to balance when we start the journey of practicing meditative concentration.

iii. Meditative Concentration in Daily Life

But is the perfection of meditative concentration only about sitting meditation? Actually, no. Sitting meditation is only one part of it. The more important side is, how can we maintain that same state of calmness that we achieved in meditation even in our daily life?

To put it in everyday scenario, how can we practice meditative concentration when we are driving a car, buying groceries, working in office, working at home, taking care of children, cooking… you name it. If we can maintain that same calmness when we are arguing with our coworkers, stuck in traffic, juggling three jobs at once, then we are true bodhisattva practitioners.

iv. Chan Story on Meditative Concentration

One day, the famous Song Dynasty poet, Su Dongpo, felt enlightened after a meditation session. He immediately seize a brush and a paper and wrote a poem:

I bow to the heaven above all heavens,

Whose aura shines on the great universe;

Sitting upright on the purple-golden lotus,

Unmoved by the Eight Winds, I am.

Feeling very pleased with himself, Su Dongpo called for his servant and said, “Bring this poem across the river to Chan Master Foyin! I want to hear what he has to say!”

The servant took the poem and ferried across the river to the temple where Chan Master Foyin lived, and came back quicker than expected.

Su Dongpo interrogated his servant, “So? Did the Chan master say anything?”

“No sir.”

“What? Nothing at all?”

“Well, the Chan Master wrote something on the paper.”

“Give it to me immediately!”

Su Dongpo seized the paper immediately and searched all over it for the Chan Master’s comment. Finally, he spotted one word at the bottom of the page, and it says, “Fart!”

Su Dongpo was so angry that he ran down to the docks and ferried across the river. But just as his feet touched upon the other side of the shore, he saw Chan Master Foyin, standing at the dock and laughing heartily.

“Oh great poet! Didn’t you say are unmoved by the Eight Winds? How can a simple fart blow you across the river?”

The Eight Winds refer to praise, ridicule, defamation, honor, gain, loss, sorrow, and joy. The eight experiences in life that stir up our emotions and ignited our actions. However, if we truly practice meditative concentration, then we would not be affected by any of these experiences. We would remain calm and at ease, and even a little humorous, in face of the challenges that life inevitably brings.

III. Perfection of Prajna Wisdom

Once upon a time, five blind men were ordered by the emperor to enter the royal palace. The emperor said, “There is an animal called the elephant right in front of each of you. Feel it and tell me what the elephant looks like.”

The first blind man said, “The elephant is a wall!”

The second said, “What? The elephant is a pillar!”

The third said, “No! The elephant is a fan!”

The fourth said, “You are all crazy! The elephant is a spear!”

The fifth said, “Listen to me, the elephant is a rope!”

So what does an elephant look like? Does it look like a wall or a pillar? Does an elephant flap away like a fan or sharp as a spear? An elephant is a combination of all these descriptions, but the five blind men, hindered by their lack of sight, are unable to perceive the entirety of the elephant. Furthermore, they refuse to accept the observations of the other men and insist on their own opinions.

As stated in Buddhist sutras, “The first five perfections are like the blink in which the six perfection is the guide.” Each of the Six Perfections, no matter if it is the practice of generosity, precept, patience, diligence, meditative concentration, or prajna wisdom is extremely important to a bodhisattva, but prajna wisdom is the most important of them all.

Everyone can practice the first five perfections. These cultivations are not limited to Buddhists. However, if we practice the Six Perfections without prajna wisdom, then we will find ourselves like the five blind men, hindered by our limitations and unable to transcend to a higher level of realization.

i. What is Prajna Wisdom?

First, what is prajna wisdom? Is it different from just plain “wisdom?” In the book Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple, Venerable Master Hsing Yun describes wisdom in four levels:

1. Right View

The first level is “right view.”

Right view is prajna wisdom as understood by sentient beings. To have right view means to have correct understanding of the law of karma, or the law of cause and effect. If we have right view, we will not be easily affected by external afflictions, and naturally we will not create negative actions that are usually a reaction against external experiences.

2. Dependent Origination

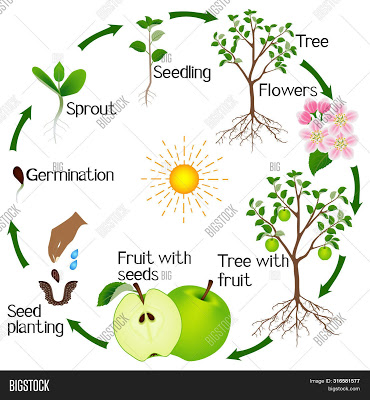

The next level of wisdom is understanding dependent origination.

This is the wisdom as understood by sravakas and pratyekabuddhas. Every phenomena is dependent in origination. They come into existences when the right causes and conditions combine, and cease to be when causes and conditions disperse. For example, a seed can sprout leaves and grow into a tree if the conditions of sunlight, water, and air are present. But if the tree could no longer reach sunlight, water, or oxygen, it would die. This is the second level of prajna wisdom, which is realizing the teaching of dependent origination.

3. Emptiness

The third level of wisdom is emptiness, which is wisdom as attained by bodhisattvas. When we realize that everything in this world is dependent in origination, we understand that the essence of all phenomena is empty. Emptiness does not mean nothing. As the saying goes, “Wondrous existence arises from true emptiness.” Only with emptiness is existence possible. Everything in the universe and in this world can come into being because of emptiness.

4. Prajna wisdom

The highest level of wisdom is prajna wisdom, which is only attained by buddhas. As Venerable Master Hsing Yun said,

Prajna is the “complete and clear wisdom of awakening” that all buddhas attain through realizing the true form of all phenomena.

Prajna is “pure wisdom without discrimination”—to be without deluded emotions or thoughts.

Prajna is “true and formless wisdom”—the direct realization of intrinsic empty nature and that there is nothing to be attained.

ii. Practicing the First Five Perfections with the Perfection of Prajna Wisdom

Do you still recall the story of the Blind Men and the Elephant at the start? What is the connection between this story and prajna wisdom? The five blind men are like the first five perfections. Without the light of prajna wisdom, the five perfections are only mundane practices. So as we practice the first five perfections, we need to be guided by prajna wisdom to perfect our cultivation.

Let’s look at how we can practice the first five perfections with prajna wisdom.

1. Prajna wisdom and generosity

How do we apply prajna wisdom in our practice of generosity?

For an act of giving to be complete, it needs three aspects: the giver, the receiver, and the given object. If any of these components are lacking, the act of giving cannot be completed.

Once there was a lady, Mrs. Jones, who helped to pay her sister’s medical bills. Her sister has been battling cancer and was finally declared cancer-free after a year of treatment. Even though Mrs. Jones was very happy that her sister pulled through, sometimes she regretted helping her sister out. Firstly, it was a big amount of money. Secondly, her sister has no way of repaying her as she doesn’t have the strength to find a job. So now, whenever Mrs. Jones saw her sister, she would casually say, “Hey sister, I’m the person who loved you the most in this world. Remember, I saved your life.”

What do you think about this? Though Mrs. Jones decided to help her sister willingly, she regretted her decision soon after and tried to manage her emotions by guilting her sister. As a bodhisattva practitioner, once we have given something, there is no taking it back. We need to let go of the three aspects of giving: there is no giver, no receiver, and no object of giving. And letting go is only possible when we practice generosity with prajna wisdom.

If we can give without being attached to “the giver, the receiver, and the given object,” then we would be a joyfully generous bodhisattva.

2. Prajna wisdom and precept

In Buddhism, precepts are code of conduct for a practitioner. Precepts guide us to be a more wholesome and compassionate practitioner.

However, sometimes we may judge other people based on the precepts we uphold. For example, we tell our non-vegetarian friends that they are creating evil karma in eating meat. Or if we see a fellow practitioner accidentally squishing an ant, we give them a hard time for it.

Precepts is a ruler that we use to measure ourselves, not other people. Precepts help us to refine our physical, verbal, and mental karmas so that we are a kinder and more compassionate person.

Therefore, we should uphold the precepts without attaching to its form. When we uphold precepts with prajna wisdom, we can benefit sentient beings.

3. Prajna wisdom and patience

Patience is a test of one’s level of endurance. But mundane patience is sometimes like a pressure cooker. You can keep it in and hold your tongue for one hour, two hours, one day, a week, or even a whole year, but one day when you cannot contain your anger or stress any longer, you may be like a pressure cooker that was used the wrong way, and explode.

This is why we need to practice patience with prajna wisdom, so that we will not be attached to the notion of self. Moreover, having patience with prajna wisdom leads one to realize the patience of non-arising dharmas. You become a practitioner who is patient without the idea of, “I am being patient.”

4. Prajna wisdom and diligence

What about prajna wisdom and diligence?

Have you ever encountered a person who said, “How many times do you chant the Buddha’s name in a day? What? Only 500? I chant 10,000 times a day.” Or, “how many hours do you meditate a day? What? Only 1 hour? I meditate 10 hours a day.”

Diligence is a virtue which we hold ourselves accountable. Diligence is our conscience that tells us never to give up and continue to strive for the better. However, sometimes we might get too proud of ourselves after we worked really hard, and think that everyone else is not as good as us.

When we practice diligence with prajna wisdom, then we will not give rise to arrogance. Moreover, we will be empowered to progress tirelessly.

5. Prajna wisdom and meditative concentration

Last but not least, how can we practice prajna wisdom with meditative concentration? As we meditate, we might reach a deep state of concentration known as samadhi. Sometimes, being in a samadhi makes us feel very peaceful and at ease, and some people might be attached to these states.

If we are attached to samadhi, then we will be stuck in the same state. We cannot progress further along the path of cultivation.

This is why we need to practices meditation with prajna wisdom so that we will not attach to samadhi. Moreover, practicing meditative concentration with prajna wisdom leads one to realize and attain buddhahood

Prajna is the guide which the other five perfections follow; without it, the other five perfections are blind. Put differently, the first five perfections are worldly Dharma practices; only by incorporating prajna wisdom do they become transcendental Dharma practices.

IV. Conclusion

As Venerable Master Hsing Yun said about the Six Perfections:

The practice of generosity: Not only does one overcome greed when practicing generosity, but it also benefits others

The practice of precept: Not only will one prevent harming oneself when upholding precept, but others as well

The practice of patience: Not only does one overcome hatred when practicing patience, but it will also not harm others out of hatred.

The practice of diligence: Not only does one overcome indolence when being diligent, but it also teaches others not to be indolent.

The practice of meditative concentration: Not only does one overcome a scattered and distracted mind when practicing meditative concentration, but it also teaches others not to be distracted and unfocused.

The practice of wisdom: Not only does one overcome ignorance and deviant views with prajna wisdom, but it also teaches others to overcome ignorance and deviant views.

The Six Perfections are a positive practice of bodhisattvas. It is a very profound practice, for it helps one to establish wholesome Dharma in life, to preserve a continuous enthusiasm for learning in life, and to finally reach the ultimate shore of perfection.

That’s all for this episode. Thank you for listening.

Next week, we will begin a new mini-series called Introduction to Meditation. If you want to learn more about practicing meditation, stay tuned to our future episode.

May you find peace and joy in the Dharma. Omitofo.

Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple 1

In today’s Buddhist sphere, numerous claims have been made on what the Buddha has taught. However, were they truly spoken by the Buddha? The Buddha-Dharma: Pure and Simple series is an exploration of over 300 topics, where Venerable Master Hsing Yun clarifies the Buddha’s teachings in a way that is accessible and relevant to modern readers. Erroneous Buddhist views should be corrected, the true meaning of the Dharma must be preserved in order to hold true to the original intents of the Buddha.

Published by: Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

Read it here