Speaker: Venerable Hui Cheng

Fo Guang Shan Qishan Temple

I. Introduction

Auspicious greetings to our friends around the world. This is Hui Cheng from Fo Guang Shan Monastery in Taiwan. I hope that this online session of Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services finds you well.

Last week’s session introduced the importance of Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem and making vows for meditation in fostering the right mental equipoise for sustained practice, and that being mindful of the body in our daily lives grounds us in the here and now, and is the entry point to meditation.

We also learned that śamatha works to develop a deep, static state of one-pointed concentration on an object of focus, and leads to samādhi, a state of mental tranquility that is unperturbed by either internal or external disturbances. The graduated practices of śamatha include Relaxation, Breath Counting and Breath Observation. The three techniques are used to release built-up bodily tension, quieten both breath and mind, and eventually turn the focus of the mind onto itself.

The process of resetting the focus on the object of meditation whenever the mind wanders trains us not to be taken away by our sensations, emotions and delusive thinking. This important skill developed on the meditation cushion is carried over into one’s daily life.

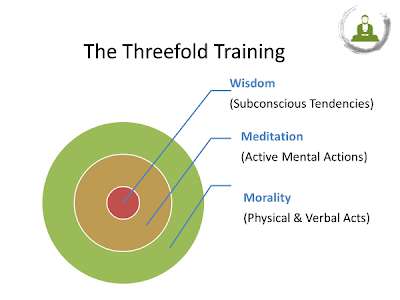

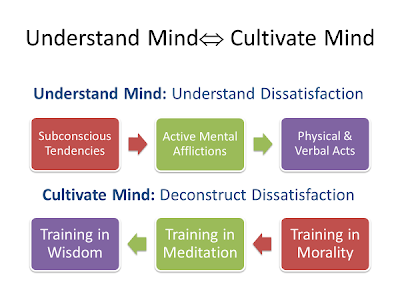

To recap, in relation to the Threefold Training, the Training of Morality addresses the coarse and overt occurrences of the mind through body and speech, while the Training of Meditation addresses the finer active mental activities based on observation of the breath. The Training of Wisdom addresses the finest occurrences of the mind, that is, the latent tendencies of the subconscious mind by removing dormant seeds of affliction and planting pure seeds of wisdom and compassion.

The practice of vipaśyanā works on the levels of Training of Meditation and Training of Wisdom, as both the effort and the result. It develops sharp insight that cuts through all afflictions.

II. Understanding One’s Subjective Experience of Life-identity and the notion of “I”

This week, we will be covering the requisite understandings for the practice of vipaśyanā or insight meditation, in relation to human sentience and the sense of identity or self. With the establishment of morality as the overt manifestation of conventional right view, and concentration through the practice of śamatha, one has the supporting framework and focus to begin contemplating the Dharma in a steadfast manner.

Vipaśyanā aims at purification of mind by gaining insight into the real nature of all phenomena, seeing the impermanence, suffering and non-self of things through the Four Bases of Mindfulness.

The Four Bases of Mindfulness are one’s body, one’s sensations, one’s mind, and mental objects. Mindfulness here refers to a moment to moment awareness, that is applied to all spheres of our everyday lives. This awareness builds momentum and becomes continuous as we make it a habit to engage in the practice.

Before we can fully appreciate the merits of this practice, it is necessary to first establish an understanding of the human subjective world experience, that is, to familiarize ourselves with what creates our underlying sense of being. The Buddhist understanding of this is based on the Five Aggregates (Sanskrit: skanda) and divides sentient life into five psychophysical elements of form, sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness.

Of the five, form is the only physical element, while the other four are mental factors. This body/mind complex is what we consider the “I”. However, by not understanding the interdependence of the elements that make up this sense of being, it is easy to establish an inverted sense of self as monolithic entities that are autonomous and independent. We create this conception of self that we actively enforce and defend, giving rise to desire and aversion.

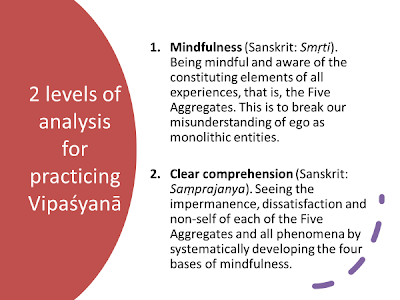

From the Buddhist point of view, the way to true joy and awakening is to see through our basic clinging to that stronghold concept of self, which is also known as ego. To do that we have to find out what ego is. We also need to introspect and see how ego operates within ourselves, so that we may prescribe methods of practice to address the ego. This sense of self manifests at different levels of the mind. As such, one may consider 2 levels of analysis for practicing vipaśyanā:

1st level: Mindfulness (Sanskrit: Smṛti)

Being mindful and aware of the constituting elements of all experiences, that is, the Five Aggregates. This is to break our misunderstanding of ego as monolithic entities.

2nd level: Clear comprehension (Sanskrit: Saṃprajanya).

Seeing the impermanence, dissatisfaction and non-self of each of the Five Aggregates and all phenomena by systematically developing the four bases of mindfulness.

This session will be elaborating on the mindfulness of the five aggregates.

III. Five Aggregates

Sensation(Sanskrit: vedanā) refers to passive sensory function which senses an object as either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. As our eyes, ear, nose, tongue and body comes into contact with the outside world, five corresponding objects of sight, sound, odor, taste, and tactile sensations appear. These corresponding objects are associated by the 2nd aggregate as either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral sensations. The same is true for the mind faculty and the corresponding object of thought.

Feelings of hunger, physical pain, heat, and cold are examples of sensations that are perceived as unpleasant, while breathing is normally associated as a neutral sensation. The sensation of being satiated or hydrated is usually associated with pleasant sensations. Likewise, the thought of physical comfort is pleasant. The aggregate of sensation does not produce either wholesome or unwholesome karma. They are just natural responses of the human condition based on survival instincts, bodily needs, and human ecology.

Form (Sanskrit: rūpa) entails the human body as well as external material form. “Form” refers to anything that obstructs, that is, anything that occupies space, can hinder or obstruct, or can be divided into parts. They are the first five faculties (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body) and the first five corresponding objects (sights, sounds, odors, tastes, and tactile sensations. Simply put, everything you see, hear, smell, taste, and feel is considered form.

Sensation (Sanskrit: vedanā) refers to passive sensory function which senses an object as either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. As our eyes, ear, nose, tongue and body comes into contact with the outside world, five corresponding objects of sight, sound, odor, taste, and tactile sensations appear. These corresponding objects are associated by the 2nd aggregate as either pleasant, unpleasant or neutral sensations. The same is true for the mind faculty and the corresponding object of thought.

Feelings of hunger, physical pain, heat, and cold are examples of sensations that are perceived as unpleasant, while breathing is normally associated as a neutral sensation. The sensation of being satiated or hydrated is usually associated with pleasant sensations. Likewise, the thought of physical comfort is pleasant. The aggregate of sensation does not produce either wholesome or unwholesome karma. They are just natural responses of the human condition based on survival instincts, bodily needs, and human ecology.

Preception (Sanskrit: saṃjñā) is a busy aggregate yet a passive one. Most of what we call thinking fits into this aggregate. It automatically provides abstract ideas of what things are through language, knowledge, and so forth, and functions by registering, recognizing, and associating our experiences. When we see, hear, smell, taste, or touch something, we always flip through our mental index cards to find categories we can associate with the new object. For example, when we see a doctor, we associate him/her with our previously constructed knowledge of what a doctor entails, together with our experiences of interacting with them. Likewise, if we have ever touched a hot stove in the past, we will recognize that touching a hot stove results in the sensation of pain, and so we associate touching a hot stove with pain, and will establish the knowledge that hot stoves should not be touched.

In a similar way, all types of learnt theories are the product of this aggregate. For example, no one is born a racist or sexist. These mindsets are learned from society. As such, it is important to establish correct knowledge and associations, as future experiences and decisions are shaped by them. Therefore, right views are imperative. If we develop wrong views, all subsequent recognition and synthesis of new experiences become distorted.

Apart from conceptualizing present experiences by making associations and recalling the past, the 3rd aggregate also imagines the future. Planning, thinking, and anticipating are examples of how this aggregate works into the future. We may plan our schedule for the next day or anticipate outcomes based on previous experiences. These are the workings of this aggregate. In and of itself, the aggregate of perception is largely not problematic. It works passively to make sense of the world. It is the working of the next aggregate that creates either wholesome or unwholesome karma.

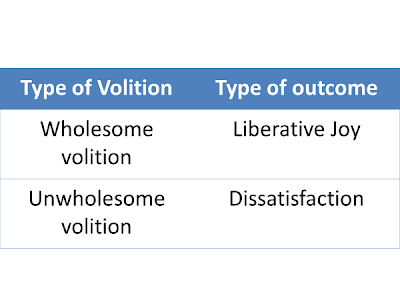

Volition (Sanskrit: samskara) can be understood as active mental actions or formations that are driving forces. These include all types of active emotions, mental habits, opinions, and decisions triggered by an object of experience. When we refer to wholesome and unwholesome states of mind, we are referring only to this aggregate. As for unwholesome emotions, whenever we experience something pleasant, we may have an underlying tendency towards desire and craving. When we have an unpleasant sensation, we have an underlying tendency towards aversion and hostility. In simple terms, volition conditions our likes and dislikes.

These latent tendencies manifest when volition relates experiences to our sense of “I”. Volitions justify that “I” deserve pleasant sensations, and “I” should be free of unpleasant sensations. However, when we lose access to pleasant sensations, we feel that “I” am at a loss. Whenever we are in the presence of things that cause unpleasant sensations, this sense of “I” feels violated. Either way, these afflictive states of mind cause dissatisfaction.

We also attribute this sense of “I” to objects, for example, we may say that this is “my book”, “my pen”. Where previously perception recognizes that a thin, long object that contains ink is called a pen, volition claims ownership of it. We also take ownership of opinions. “That is my opinion.” So, whenever we lose things that belong to us, or when someone has opposing opinions, we feel that the “I” is at a loss, and we start justifying our position with actions. For example, when we find out that our friends have different political views, we soon may find ourselves unfriending them on Facebook and crossing them off our Christmas card list. On a larger scale, groups of people develop hatred for one another due to opposing interests and opinions. This is the real reason behind racism, inequality, conflict, and war.

In terms of mental habituations, latent karma contained in volition inspires us to either repeatedly seek the things we crave and despise unpleasantries.

For example, when we eat chocolate for the first time, the second aggregate passively detects a pleasant sensation, while our perception helps us make sense of the experience, recognizing that chocolate is a food that tastes sweet, is brown in color and is of a particular aroma. It is volition that creates that sense of craving for the pleasant sensation, justifying ownership of it. This in turn conditions the mental habit of craving for chocolate every time we think about it or come in contact with it. It becomes almost automatic if we do not intervene. When we physically act out and eat the chocolate while inspired by craving, we allow our volition to entertain itself, reinforcing the associated latent karma of greed that accumulates over many lifetimes.

The same is true with our interpersonal relationships. Those we develop resentment for are labeled as enemies, whom when every time they appear in our thoughts or in person, causes us to habitually despise them.

More so, whenever there is that sense of “I”, then there will be the notion of “you” and “them”. Whatever is related to the “I” becomes of primary importance while things related to “you” and “them” become less important. The same is true for our opinions in relation to the opinions of others. This is how volition inspires self-centeredness.

In short, unwholesome volition includes craving, aversion, jealousy, pride, and attaching to the notion of “I”. They result in dissatisfaction. Wholesome volition includes good intentions, well-wishing, acts of compassion, selflessness and generosity. They result in reinforcing wholesome latent karma required for the practice of morality, meditation and wisdom. Unwholesome volition, in the sense of the Middle French word émotion or “mover” is precisely what vipaśyanā addresses. It is trying to calm that which unwholesomely moves the mind.

Consciousness (Sanskrit: vijñāna) is the bare act of awareness without the overlay of sensation, perception, and volition, and takes place only when the six faculties come in contact with their corresponding objects. When we see, the bare act of seeing is visual consciousness. When we hear, the bare act of hearing is auditory consciousness. The same is true for smell, taste, touch and mental processes. In a sense, consciousness is a reaction that has one of the six faculties as its basis and one of the six corresponding phenomena as its object.

At the same time, consciousness underlies all other aggregates, since without consciousness, the six faculties cannot function, and thus sensation, perception and volition do not come into play. As meditators, we slowly work towards seeing that our aggregates are continuously working, and that consciousness is actually infinite individual acts of consciousness, one after another, as we come into contact with phenomena. This means that with each arising of consciousness, we are reborn, and as such, we have unlimited potential to transform ourselves for the better.

VI. Conclusion

To recap, session 4 has covered the requisite understandings for the practice of vipaśyanā or insight meditation, that is, the Buddhist understanding of human subjective world experience based on the five aggregates. The five aggregates divide sentient life into five psychophysical elements of form, sensation, perception, volition, and consciousness. This body/mind complex is what we consider the “I”. However, by not understanding the interdependence of the elements that make up this sense of being, it is easy to establish an inverted sense of self as monolithic entities that are autonomous and independent, of which we actively enforce and defend, giving rise to desire and aversion.

In the early stages of meditation, we may not have the clarity of mind to notice how the five aggregates work in response to contact with the outside world. We seldom notice whether we react to situations based on sensation, perception, or volition. As our mind becomes calmer with meditation, we become clearer with how the aggregates work, and with this clarity, we are empowered to choose how we react to situations, and not give rise to unwholesome volitions. We are also inspired to cherish every moment of our lives to better oneself. More importantly, mindfulness of the five aggregates prepares us for the second level of vipaśyanā practice, that is, the clear comprehension of the five aggregates through the Four Bases of Mindfulness.

Thank you for joining us for session 4 of the mini-series on meditation. Session 5 will conclude the mini-series with an introduction to the second level of vipaśyanā practice, that is, the clear comprehension of the five aggregates through the Four Bases of Mindfulness. If you find this Dharma service beneficial to your practice, please subscribe to the FGS English Dharma Services YouTube Channel and share it with your friends. May the merits of this session bless you with the conditions conducive of right meditation and wisdom. See you next week, Omituofo.