Speaker: Venerable You Lu

Fo Guang Shan Buddha Musuem

I. Introduction: The Buddhist Literary Genre of Avadana

Hi everyone, good evening and thank you for tuning in to English Dharma Services. This is You Lu from the Buddha Museum and for the next four weeks, I will be talking about Purnavadana, or the Story of Purna.

“Avadana” is a term used to denote a type of story found in both Buddhist and non-Buddhist literature. Avadanas typically exhibit a three-part narrative structure, with a story set in the present context, and a story set in the past; these two stories are then connected when the past actor is identified as a prior incarnation of the main character in the present. In contrast to the jatakas (records of the Buddha’s past lives), the main character in an avadana is generally not the Buddha, but rather, someone who is a follower of the Buddha, or someone who will become a follower.

Avadanas are one of the twelve categories in Buddhist literary genres and correlate a person’s past with his or her present deeds, either lay or ordained, and who, in some specific fashion, exemplifies Buddhist ethics and practice.

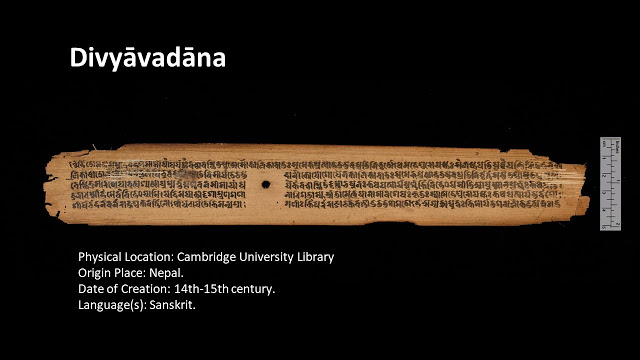

The Divyavadana

The Purnavadana appears as the second of 38 narratives in the Divyavadana. Divyāvadāna, which translates as “Divine Exploits” in Sanskrit, is a collection of thirty-eight “heroic tales” or “narratives”.

The present characters in the Divyāvadāna stories are often identified as persons whom the Buddha encountered in a former life. Thus, these tales are narrated in similar structure as the Jataka stories, in which an event in the present offers an opportunity to recount a story from the past, which in turn illuminates details regarding present circumstances. Themes that run throughout the Divyāvadāna include:

- The realization of positive or negative consequences of karmic action

- The importance of moral discipline

- The great merit that can be accrued through service or reverence offered to the buddhas, or to sites related to the buddhas, such as a stupa.

The Divyāvadāna includes thirty-six avadānas and two sutras (teachings of the Buddha). There are several famous stories found in the Divyāvadāna collection. One of them is the Pūrṇāvadāna, or the story of the monk Purna. The Asokavadana recounts the birth, life, and reign of King Asoka, a monarch highly revered in the Buddhist tradition as a great protector of the religion. Although there may be differences in style and language, more than half of the tales appear in the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya (The Buddhist book on monastics’ code of conduct).

This association with the Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya suggests that these stories could date as far back as the beginning of the Common Era. However, the oldest extant manuscript of the Divyāvadāna dates only to the seventeenth century, and no earlier Buddhist reference could be sourced. There is also no Tibetan or Chinese translation of the text, although many of its stories are found in the Tibetan and Chinese canons. (For example, twenty-one of the thirty-eight stories of the collection are found in the vinaya section of the Tibetan canon.) This has led some scholars to conclude that, although the stories themselves are old, the compilation of the Divyāvadāna may have taken place much later.

The Divyāvadāna legends held a significant influence on Buddhist art and were often the subject of Buddhist sculptures and paintings. For instance, in the “Sahasodgata” chapter of this collection, the Buddha describes the “wheel of existence” (bhavacakra), which became a popular subject of painting in many of the Buddhist traditions.

The Purnavadana is one of half a dozen avadanas found in all the extant recensions of the Divyavadana. The Purna-story is also found in the Tibetan translation of the MulasarvastivadinVinaya, in a number of versions in the Pali commentaries, and elsewhere.

I found a similar narrative in the Chinese Sutra, Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish, in the chapter “The Tale of Purna” (富那奇緣品). The Sutra of the Wise and Foolish is a collection of jatakas and avadanas that related the karmic consequences of wise and foolish acts. The sutra consists of 13 fascicles, and the Chapter of “The Tale of Purna” (富那奇緣品) is recorded in the third of four chapters in fascicle six.

I referred to the book The Deeds of Purna: A Translation and Study of the Purnavadana by Joel Tatelman and Divine Stories by Andy Rotman for the English translation. And I will make a few comparisons between the Purnavadana and the Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish in the Fo Guang Buddhist Canon, as we go along.

II. The Story of Purna: Purna and His Family

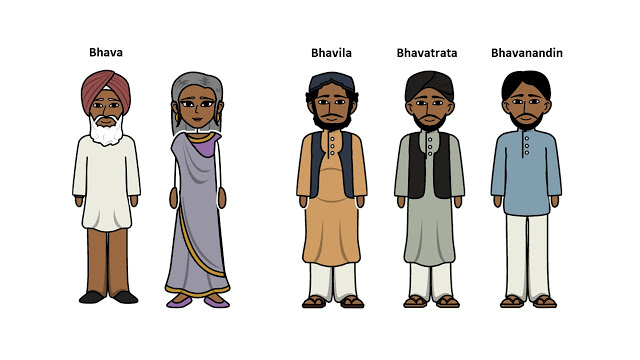

The Purnavadana begins with the introduction of Bhava, a wealthy householder, who lived in Surparaka with his wife and sons: Bhavila, Bhavatrata, and Bhavanandin.

One day, Bhava fell sick, and because of his abusive language, his family abandoned him. As they left, a slave-girl remained behind in the house and took care of Bhava. She got him some medicine and eventually Bhava regained his health. Bhava reflected on how his family abandoned him and how the slave-girl took good care of him. He decided to reciprocate her kindness. He asked what she would like to have as a reward, and she replied that she would like to have a son with him. She reasoned that this was the only way that she can be freed from the slave caste, by having a relationship with an Aryan. So they slept and the slave-girl gave birth to a boy after nine months.

The baby boy was good-looking, handsome, with fair complexion, and had an umbrella-shaped head, long arms, a broad brow, eyebrows that joined, and a prominent nose. The boy was named Purna and was taken care by eight nurses.

When he grew older, Purna was instructed in reading and writing, arithmetic, accounting, finance, debt-collection, commercial law as well as in the inspection and assessment of jewels, property, elephants, horses and young men and women. In these eight examinations, he became an eminent authority, wise and skilled in the traditional learning.

At a young age, Purna had shown an adeptness in running business. When his brothers went out across the ocean to trade, he was asked to look after the family business due to his young age. When his brothers returned from their business trips, Bhava tallied the profits that each of them had earned, and Purna had earned even more than what his brothers had.

After some time, Bhava sensed his imminent death and thought up a strategy to keep the family undivided. He instructed his eldest son, Bhavila, to take care of Purna. Not long after, Bhavatrata and Bhavanandin proposed to split up the house, the family business, and Purna among the three of them. Because Bhavila had been instructed to take care of Purna, he chose Purna over the house and family business. After that, Bhavila and Purna were driven out from their family house and shop, and they set out to live with their relatives.

III. Purna and the Sandalwood

One day, Purna was asked to get breakfast for Bhavila’s sons. He went out to the market and found a man who was trembling as he was carrying a load of wood. Purna was expert in the assessment of different types of wood. He began to examine that load of wood and saw that it was gosirsa sandalwood. Purna bought the sandalwood with 500 karsapanas (silver coins) and cut up the wood into four smaller pieces, each to be made into fragrant powder and sold at double the price.

Some time later, the king of Surparaka became afflicted with a high fever. His physicians prescribed gosirsa sandalwood, and so his ministers undertook a search for some. Eventually, they found Purna, who sold gosirsa sandalwood to the ministers at one thousand karsapanas. We can see that Purna is pretty good in doing business.

Back in the palace, an ointment prepared from the sandalwood was applied to the king’s body, and he regained his health. The king remarked: “The gosirsa sandalwood is hard to get, from whom did you get it?”

“Lord, from Purna,” answered the ministers.

The king was curious about this person, so he said to his guards, “Summon Purna to me.”

IV. Purna and the King

Later, a messenger from the king arrived and announced for Purna, “Purna, the king summons you.”

He began to think: “Why has the king summoned me?” And then it occurred to him, “It is because of the gorsirsa sandalwood that the king has regained his health. That is why he summons me. Well, I certainly must take along some of the gosirsa sandalwood when I go.”

Having wrapped three pieces of the gosirsa sandalwood in a cloth, and carrying one piece in his hand, Purna went before the king.

The king asked him: “Purna, do you have any gosirsa sandalwood?”

“Lord, I have one piece,” said Purna.

The king would like to acquire more sandalwood. “What is the price?” he asked Purna.

“Lord, a hundred thousand suvarnas (gold coins),” said Purna.

“Do you have any more?” asked the king.

“Yes, Lord, I do,” and Purna showed the king the other three pieces. The king gave a command to his ministers, “Give Purna four hundred thousand gold coins.”

Purna said, “Lord, give three hundred thousand. One piece is a gift to my Lord.” And so Purna was given three hundred thousand suvarnas.

The king said: “Purna, I am extremely pleased. Tell me, what boon shall I give you?”

Purna replied: “If my Lord is pleased with me, may I be permitted to live in your kingdom undisturbed?”

The king gave a command to his ministers: “From this day forth, you may give orders even to the crown princes, but not to Purna.”

V. Purna and the Merchant Guild

At the same time, there were 500 merchants who arrived in Surparaka on ships laden with treasures. The merchants’ guild at Surparaka had a rule that people are not allowed to purchase goods directly from the merchants, only the guild can do that. However, Purna approached the merchants and bought all the goods with a deposit of 300 thousand golden coins.

Some time later, agents from the merchants’ guild came to see the merchants, and was told that the goods were sold to Purna. The agents returned to the merchants’ guild and levied a fine of 60 silver coins against Purna for going against the guild’s rule.

The king’s officers saw what happened and reported this incident to the king. The king then summoned Purna and the members of the guild, and when asked about the levy, Purna spoke up saying the guild had set a rule without informing him or the other merchants. When the king asked the members of the guild if that was true, they replied, “Yes,” and the fine was dropped.

VI. Purna Goes to the Sea

Some time later, Purna decided that he should cross the ocean to gather trade-goods for himself, and having earned a name in the business field of Surparaka, he attracted 500 merchants to make the journey with him. He crossed the oceans six times, and each time, his ship was filled with riches. When the 500 merchants asked to cross the oceans for the seventh time, Purna decided that he would no longer seek for wealth, but would still cross the ocean with his 500 companions.

On this trip, there was one night, during the time before dawn, those merchants recited passages aloud and at great length. These are verses from the sutras.

Purna listened to them, and said, “Sirs, you sing beautiful songs.”

They replied: “Great caravan-leader, these are not mere songs. You must know that these are the words of the Buddha.”

Upon hearing the name “Buddha,” which he had never heard before, Purna got goose-bumps all over. All attention, he asked, “Sirs, who is this person named ‘the Buddha’?”

They told him, “There is a sramana by the name of Gautama, a prince of the Sakya-lineage who, having cut off his beard and hair and donned yellow garments, with right faith went forth from his home into the homeless life. He has fully awakened to supreme, perfect enlightenment. He, O great caravan-leader, is called ‘the Buddha’.”

The Chinese Version of Purna Goes to the Sea

The Chinese Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish had a different version to this part of the story.

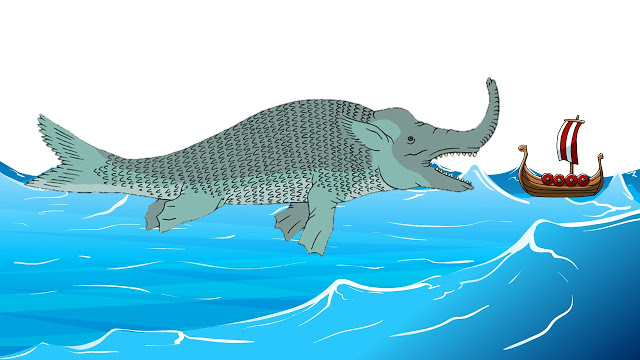

After the merchants had accumulated trade-goods as planned, they were returning from their voyage when they saw a sign at sea—there were three suns rising from the horizon.

One of the merchants on board remarked that one of them is the actual sun, and the second sun is the eye of a makara (a legendary creature in India that has the features of a crocodile, fish and elephant). The third sun is the fangs of a makara, which means they are heading toward makara, and it is going to swallow them up when they go near it.

At this time, a merchant who was a Buddhist asked everyone to recite the name of the Buddha immediately. The merchants then began to recite the Buddha’s name, and when makara heard the word “Buddha”, it closed its mouth and sank deep into the ocean. The merchants were freed from danger and they were able to return home safely.

Although there were two different versions of the story, what is consistent is that Purna was introduced to Buddha through his name. We can see from here that reciting the Buddha’s name is meritorious and even saves one from danger, and we also find something similar in the “Chapter of Universal Gateway”, in which the Buddha told Aksayamati Bodhisattva that if there be countless hundreds of millions of billions of living beings experiencing all manner of suffering who hear of Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva and call his name with single-minded effort, then Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva will instantly observe the sound of their cries, and they will all be liberated.

In fact, it was recorded in the scriptures that Buddhas had their names made known to sentient beings so that these beings would be benefited when their names are recited. For example, it was recorded in the Sutra of Infinite Life (Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra), that when Amitabha Buddha was still practicing as a bodhisattva, he made forty-eight vows to liberate sentient beings. One of these vows was that, if he became a Buddha, all beings who recite his name will be able to be reborn in his Pure Land.

And in this story, just by reciting the Buddha’s name, it had saved Purna and his companions from danger. That implies the power of the Buddha’s name and that is also why recitation of the Buddha’s name has evolved to become a Buddhist practice, especially in the Pure Land school. This also shows that all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas will not hesitate to help when their names are called.

Venerable Master Hsing Yun has composed a song titled “叫一聲,應萬聲” which means when one calls the name of Avalokitesvara once, and the call will be responded in ten thousand ways.

VII. Purna Seeks to Renunciate

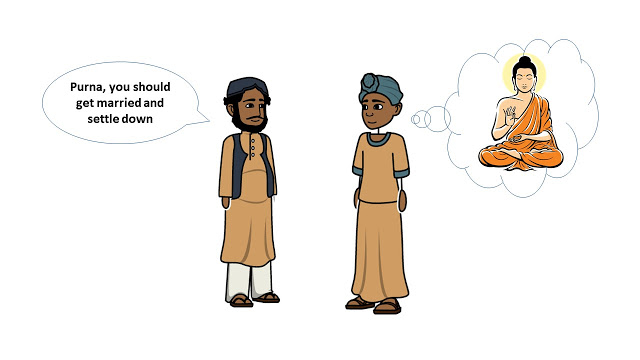

After Purna came back with more wealth gathered from the voyage, his brother Bhavila thought he should get married and settle down. And so Bhavila told his brother, “Purna, tell me which of the two I should ask on your behalf for his daughter in marriage—a wealthy merchant or a caravan-leader.”

Purna replied, “I am not seeking love. If you would permit it, I shall go forth from the life of a householder into the homeless life.”

Bhavila said, “When in our home there was no business, you did not go forth into the homeless life. Why do you want to go forth now?”

Purna told him, “Brother, then it wasn’t the right thing to do, but now it is appropriate.”

So having heard the name “Buddha,” Purna was determined to become a renunciate. But would his brother Bhavila agree to his request? We will find out next week.

Thank you for tuning in again and if you haven’t subscribed to this channel, please remember to press the subscribe and hit the bell button so you would be notified on the latest updates. Goodnight and see you next week!