Speaker: Ven. Zhi Tong

Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism

I. Introduction

Auspicious greetings! Welcome back to another episode of Fo Guang Shan English Dharma Services. This is the third and final episode on Master Kumarajiva.

Last week, we learned how Master Kumarajiva was forced out of his homeland and brought to China. But unfortunately, he was unable to advance further into the land as there were political changes. We also learned how Master Kumarajiva was humiliated and challenged by the Chinese general Lu Guang, and was kept hostage by him in the land of Liang Zhou for sixteen years.

II. Part 7: Arrival to Chang’an

Now, let us turn our lens back to the Chinese city of Chang’an again. When we last saw Chang’an, the king was still Fu Jian, who was also the king of General Lu Guang. But now, the king was named Yao Xing. Yao Xing’s father was actually a minister in the court of King Fu Jian, but a defeat in a major battle led to political struggles on many sides, and Yao XIng’s father emerged victorious as the new king.

Just like King Fu Jian, King Yao Xing was a devout Buddhist. Perhaps he had heard of the great name of Master Kumarajiva from the eminent Master Dao’an, who we have met in the last video. Master Dao’an had, at this time, passed away for nearly sixteen years now, for the time as long as Master Kumarajiva had been kept in Liang Zhou. King Yao Xing did not forget Master Kumarajiva, and had even repeatedly invited Master Kumarajiva to Chang’an, but he was detained by Lu Guang, and even after Lu Guang’s death, his successors held Master Kumarajiva in Liang Zhou.

At last, King Yao Xing sent an army to crush Liang Zhou and get Master Kumarajiva. In the year 401, Liang Zhou succumbed to King Yao Xing, and Master Kumarajiva was finally on his way to Chang’an.

What happened to Master Kumarajiva during his sixteen-year-captivity in Liang Zhou? Not much is known about that period, but it was guessed that Master Kumarajiva seized the chance to perfect his Chinese language skills and of course, deepened his understanding of the Buddha-Dharma. The sixteen-year period had not been in vain. At last, at the age of 57, Master Kumarajiva reached the prosperous city of Chang’an. He was brought to the King Yao Xing, who treated him with the respect and reverence of a national master. Very quickly, King Yao Xing invited Master Kumarajiva to stay at the Xiaoyao Gardens, which was part of the royal estate. The king also gathered all the knowledgeable monastics and government officials in the land and brought them under Master Kumarajiva to revive Buddhist translation.

III. Part 7: A Royal Translation Court

This was the very first Buddhist translation effort that had received complete royal patronage. In the past, Buddhist translations were done by foreign monastics, usually from the Western Regions and India. This was the initial effort of spreading Buddhism in China. The translations were done by a small group of people, receiving patronage only from Buddhist devotees or benefactors. Without large-scale support, the spread of Buddhism was slow.

This changes with Master Kumarajiva’s translation court. The scale and planning of his court served as a model for similar endeavors in the future. Under such troubling times, Master Kumarajiva’s court had an amazing assembly of three thousand people.

It is important to mention that several of the most eminent members of the court were actually the disciples of Master Dao’an. They were originally part of Master Dao’an translation court, but when the previous kingdom fell, all Buddhist endeavors came to a halt as well. It wasn’t until the arrival of Master Kumarajiva that such a great endeavor was revived again. Furthermore, they remembered Master Dao’an’s wish to invite Master Kumarajiva to Chang’an, so they could learn and benefit from his profound wisdom as well. Hence, some of the most important members of Master Kumarajiva’s translation court were Master Dao’an’s disciples.

What was the structure like in Master Kumarajiva’s translation court? How did thousands of people come together as a cohesive team to produce some of the most popular sutras in Chinese Buddhism?

Let us take a look at the translation procedure:

- First and most obviously, they need to have obtain Buddhist texts. During those time, books are extremely hard to come by as printing had yet to be invented. Hence, everything were hand-written. Furthermore, poor transportation methods means that it was not easy for one to access Buddhist texts as people would need to carry it all the way from India, through the Western Regions, before the texts could arrive to China. Hence, the ways Buddhist texts are obtained are either by foreign monks travelling from the West to China. They might bring hardcopies with them, or they had memorized entire Buddhist texts. The second way was that the texts were brought back by Chinese monks who had travelled back from the West. These texts could be written in Sanskrit or any of the languages spoken in the Western Region countries.

- Upon choosing a Buddhist text to translate, Master Kumarajiva would first explain sutra text. From this, we can see that Master Kumarajiva was proficient in a lot of languages. He would explain the text in Chinese, and expound the deeper meaning behind written words repeatedly, so that the present company understood the text. This prepared them for the translation work.

- Next, Master Kumarajiva would do sight interpretation, which means he would read the Buddhist text in its original language, and interpret the content verbally. His verbal interpretations were recorded by scribes.

- The first round of translation had to be re-examined. Master Kumarajiva continued to explain the text and answer any questions or doubts from other members of the court. Master Kumarajiva emphasized on translating the accurate meaning of the text, instead of the words themselves.

- All spoken interpretation and discussions were recorded, and these notes were compared to determine the final draft of translation

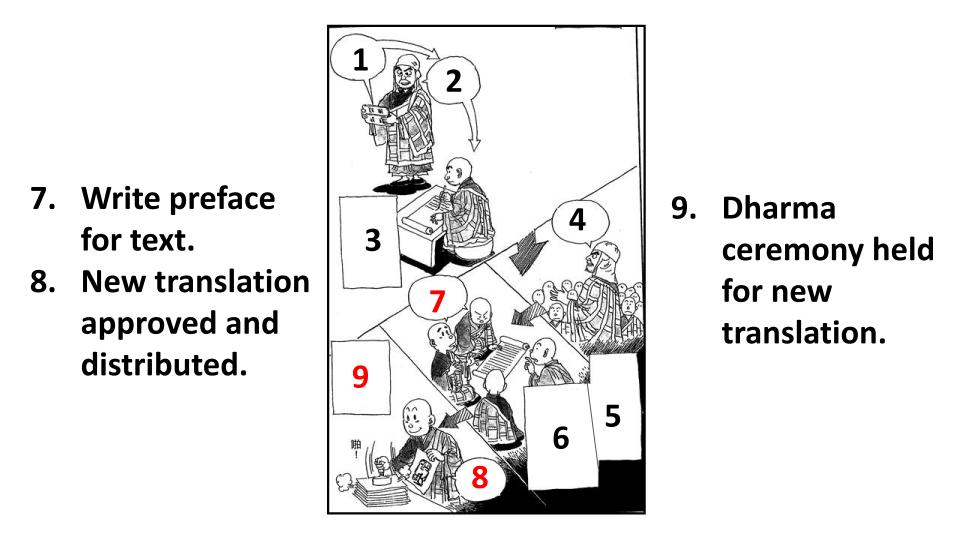

- Once the final draft was determined, the text underwent repeated editing and corrections before the ultimate translation was read and approved by Master Kumarajiva.

- When the final translation was approved, a preface of the text was written to explain the main ideas of the text, as well as its importance in Buddhism. The preface also recorded the translation team and the processes that the team went through in producing the final result

- The new translation, along with its preface, was copied and distributed. As previously mentioned, printing was not yet available, hence all sutra books were hand-copied,

- To celebrate the event of a new translation, a grand offering ceremony was held. Sutras are considered the Dharma Gem of the Triple Gems of Buddhism, hence every new translation was treated with the utmost respect. Master Kumarajiva would also held great lectures for thousands of people on the new translation, so that not only everyone could learn about the sutra, but they could also promote and propagate the sutras as well.

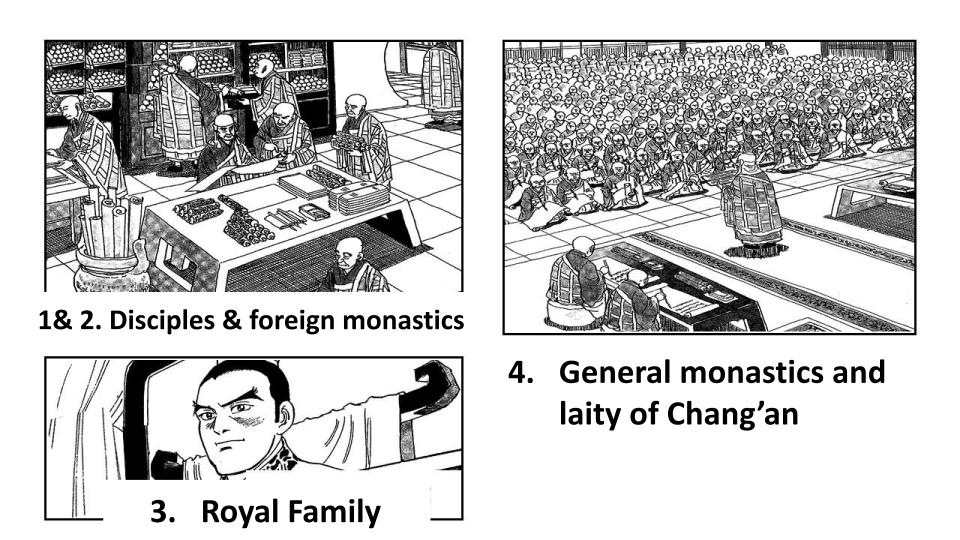

What kind of people were in Master Kumarajiva’s translation court? There were four kinds: (1) Master Kumarajiva’s disciples, (2) eminent masters from Western Regions and India, (3) the royal family, and (4) general monastics and laity of Chang’an.

- First was Master Kumarajiva’s disciples. They were the the most important members of the translation court, and they were tasked to write down what was said/interpreted by the master, editing, polish translation, and write preface for a finished text

- The second group of people were Buddhist masters from Western regions. They would bring Buddhist texts with them to China, either in the form of books or their memory. If it was from their memory, they would recite memorized texts, which Master Kumarajiva would interpret. More importantly, sometimes even Master Kumarajiva needed time to contemplate over some of the more obscure meaning of the text, and he would engaged in discussions with these monks to clarify the doctrines.

- The royal family were not only patrons of the translation court; some of them were active participants in the translation procedure. For example, King Yao Xing and his brothers also joined in the translation process as scribes when they could. The royal family were devout Buddhists, and showed their greatest support towards all Buddhist endeavors.

- Last but not least, general monastics and laity of Chang’an. As the number of monastics began to grow, King Yao Xing saw the need to regulate monastic lives. Hence, he appointed some of the Buddhist monastics as officials to look over the living of monastics, making sure everyone was living according to monastic regulations. As for laity, they were invited to the court to listen to the newly translated sutras and encouraged to raise questions about the text. This was a way to help make the translation clearer. A number of commentaries on the newly translated sutras were produced because of these discussions.

As can be seen, the translation court was an extremely lively place. Scholarly and doctrinal discussions were welcomed and held, the Buddha-Dharma was continuously debated and expounded. It was because of these invaluable efforts that shaped the future direction of Chinese Buddhism.

IV. Part 9: A Pure Lotus

A curious incident was recorded in the last years of Master Kumarajiva. [Slide 17] King Yao Xing, who had been a great supporter and devotee of the Master, was struck with a thought one day. He thought it would be a great pity that Master Kumarajiva’s intellect and ability was lost after the Master’s demise. Hence, he forced Master Kumarajiva to accept ten court ladies with the wish that an heir would be produced to continue the lineage of Master Kumarajiva.

The Master was tortured by such an order, but for the sake of Buddhism, he had no choice but to endure King Yao Xing’s nonsensical arrangement. King Yao Xing had the Master move out of the monastics’ quarters and built a new house for him and the ten court ladies.

Some less cultivated people scorned at Master Kumarajiva and held him in contempt. Some were even wild enough to believe they also merit the same treatment. To lay this matter to rest, Master Kumarajiva held an assembly. He had his alms bowl in his hands, and asked each of the monastic to place their sewing needle into his bowl.

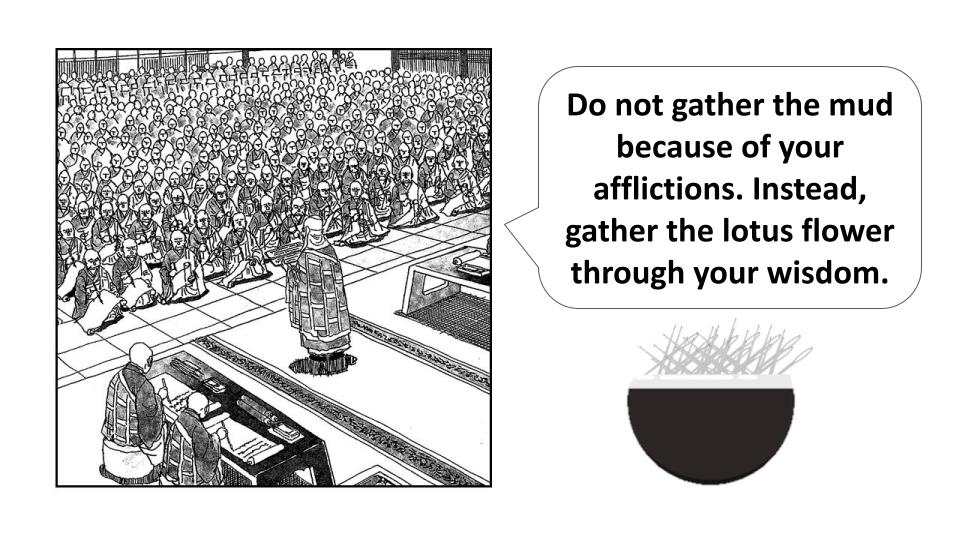

The Master spoke to the assembly, “The pure lotus flower grows from the dirty, murky mud. Do not gather the mud because of your afflictions. Instead, you should gather the lotus flower through your wisdom. If you could swallow this bowl of needles as I, then you may follow all of my actions. If you could not, then you should turn your focus back to your cultivation, and nothing else.”

The assembly stared at Master Kumarajiva in awe and in shock. Master Kumarajiva held up the bowl of needles and swallowed them as if they were a bowl of rice. He was not harmed in the slightest. The assembly were ashamed of themselves and knew they had wronged the master. From that day on, the community focus whole-heartedly on their cultivation and did not raise any doubts against the master.

Around the year 412, when Master Kumarajiva was about 69 years old, he felt unwell and knew that his death was near. Deeply distraught during his final years because he had not managed, for personal and cultural reasons, to fully inculcate China with Buddha’s Mahayana teachings, he said, “It is unspeakably sad that I am now leaving the world behind. May what I have made known and translated spread further among future generations and be fathomed fully!”

Furthermore, Master Kumarajiva vowed, “Now I truly swear before you that if I did not make any mistake in my translations, then after my body is cremated my tongue will not have been burnt.”

Soon after, Master Kumarajiva passed away. After his cremation, his tongue was found whole and unscathed.

V. Part 10: The Legacy of Master Kumarajiva

How many texts did Master Kumarajiva and his court translate, and what are their influence?

In just the short span of twelve years, they completed 74 texts totaling 384 fascicles. Texts belonging to all three categories of Buddhist scriptures, the sutras, vinayas, and abhidharmas, were translated. And many of Master Kumarajiva’s translation had far-reaching implications for Chinese Buddhism. For example:

- The Prajnaparamita texts completed the Master Nagarjuna’s Buddhist philosophy of the Madhyamika

- The Lotus Sutra became the the founding text of the Tiantai School

- The Amitabha Sutra strongly influenced the Pure Land School

- The Maitreya Buddha Sutra gave rise to the Maitreya faith

- The Brahma Net Sutra served as the basis for the spread of Mahayana precepts in China

Even until today, the most popularly recited Chinese sutras are translations of Master Kumarajiva: the Diamond Sutra, the Amitabha Sutra, the Lotus Sutra, the Vimalakirti Sutra. One of the reasons that Master Kumarajiva’s translations were more popularly received was its readability and language fluency that did not compromise the text’s meaning. When Buddhism spread to Japan and Korea, Master Kumarajiva’s translations were also as popularly received and recognized as it had been in China, thus also influencing the growth of Japanese and Korean Buddhism.

He can be considered the most influential of all classical Chinese translators largely because people from all walks of life found that his distinctive easy style—more than the style of other translators—helped them understand and contemplate the dharma. Despite the trials and tribulations he faced in life, they are the nutrients that nurtured him into a great master, just as the mud is the bed from which lotuses blossom.

Thank you for tuning in to this week’s Dharma talk. I hope you find Master Kumarajiva’s life as inspiring as I did. Before I end the video, I would like to introduce an upcoming event.

VI. Upcoming Event: The 8th Symposium on Humanistic Buddhism

From November 6th to November 8th, the 8th Symposium on Humanistic Buddhism will be held online. The Symposium on Humanistic Buddhism was founded by Venerable Master Hsing Yun and organized by the Fo Guang Shan Institute of Humanistic Buddhism. It aims to encourage interdisciplinary dialogues, stimulate creativity, and show how humanistic values can be applied within the context of issues that have arisen in contemporary society.

This year, the symposium will be co-hosted by Nan Tien University in Australia. The theme is “Humanistic Buddhist Response to Modern Crises.” 23 scholars and professionals are invited to speak across 6 panels, including Dr. Lewis Lancaster, Emeritus Professor of UC Berkeley; and social psychologist Mr. Hugh Mackay.

We would like to invite you to participate in the 8th Symposium on Humanistic Buddhism. Registration is free. Click here to learn more about the symposium. Click here to register.

Thank you for listening! May you find joy and inspiration in the Dharma. Omitofo.